Dr. Lynn Lippencot had deep blue eyes and gentle wrinkles born of age and experience, with gray hair swirled about her head in some sort of styling afterthought. She was busy, as was her staff, and her office was so harried that it always seemed to be one patient away from gridlock. Yet in the few minutes allotted for my appointment, the doctor managed to find a sense of calm, a momentary focus, and she exuded reassurance. This is what a new patient wants.

Her chemo infusion room, arrayed with oak bookshelves and overstuffed recliners with a magnificent view of the local scenery, even looked like a not unpleasant place to be. I recall, after my first visit to Lippencot in October 2003, thinking: This won’t be so bad. I envisioned bringing my lunch, catching up on my reading as the infusion proceeded, perhaps laying back for a nap as I watched the sun wash across the cliffs in the distance. Of course, I’d have rather avoided the whole thing, but everyone was telling me I had “the good cancer,” and there was nothing to worry about.

The doctor was certainly upbeat. My CLL had been discovered during a routine blood test the month before, and a subsequent flow cytometry test had come back, indicating I had what she called “garden variety CLL.” Sort of like a weed, I guess. Fortunately, I had no “B” symptoms such as fatigue or night sweats, and my platelet and red blood cell production were normal, two important factors that normally argued against starting treatment. Even a fairly high lymphocyte count, 130,000, was no cause for jumping into therapy.

But a CT scan showed a number of lymph nodes throughout my body enlarged up to 3 cm. My spleen was at 18 cm. I didn’t really know what these numbers meant, and only later would I figure out that the swelling, while of some concern, was not nearly as bad as many patients experience.

The doctor was worried, though, that a swollen node could “cut off a kidney” by closing a bile duct. Visions of kidney failure loomed, and therefore treatment was advised, she said. I could take a pill called chlorambucil, which was an older therapy, not exactly on the cutting edge, and would take some time to work. Or I could opt for fludarabine, which she described as “well-tolerated, with an acceptable toxicity profile.” Fludarabine was the “gold standard” of treatment, and it would work quickly and effectively. “I have one patient who’s been coming in every few years for ten years and getting fludarabine and he’s still going strong,” she said, reassuringly.

Dr. Lippencot would have preferred a decision from me then and there, but I asked for a few days to ponder the choices. On my way out of the office I was handed the “leukemia packet” of booklets about CLL and chemotherapy, including one produced by Berlex, the makers of “Fludara for injection,” trade name for fludarabine. On the cover there was a drawing of a woman, one hand resting on her chin, as if she were deep in thought, though not overly concerned.

It was a brave new world, but it seemed as if I would be well taken care of. Indeed, if I had only just gone along, my life would have been easier.

But probably shorter.

Cartoon chemotherapy The Fludara booklet was written at about an eighth grade level and was filled with cartoon drawings, one of which pictured B cells as looking like the monster in The Blob, a '50s horror movie classic. The booklet addressed issues of hair loss and nausea, which I had always assumed were the worst effects of chemotherapy. I could handle that, especially since I had already been losing hair for years and had gotten past my fears of baldness.

The Fludara booklet was written at about an eighth grade level and was filled with cartoon drawings, one of which pictured B cells as looking like the monster in The Blob, a '50s horror movie classic. The booklet addressed issues of hair loss and nausea, which I had always assumed were the worst effects of chemotherapy. I could handle that, especially since I had already been losing hair for years and had gotten past my fears of baldness.

But tucked into a flap in the back was the actual “package insert,” a single page with printing so small that it almost required an electron microscope to read it. Some things caught my eye. Fludarabine could be mutagenic; it could cause a coma; it leads to neutropenia, thrombocytopenia and anemia in a majority of patients; I had a 16% to 22% chance of coming down with pneumonia. There was more. And even if I wasn’t sure what all those things meant, they sounded serious enough to break through the pleasant fog that had surrounded me since leaving the doctor’s office.

The fog continued to lift as my wife, Marilyn, and I began to poke around the internet, finding further studies that raised more red flags. Indeed, the more we learned, the more we realized that there were serious questions surrounding the side effects of chemotherapy. Hair loss and nausea had nothing to do with it.

Nonetheless, with my kidney ostensibly resting uneasily beneath the Lymph Node of Damocles, I remained focused on treatment. After all, my oncologist said I needed it. And my expectations were at work, too – when you have cancer, you try to kill it. That’s what I’d always been led to believe. It’s natural, when you’re newly-diagnosed and scared, to want to do something to get as much of the CLL out of your body as possible. And this dovetails into the disposition many oncologists have to treat, even when not treating, or treating less, may be a better idea. (The "watch-and-wait" concept of doing nothing was counter-intuitive, at least at that point in my education.)

It wasn’t long be fore I stumbled across an interesting treatment prospect, outlined in the Spring 2003 Leukemia Insights newsletter from the MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. The article, accompanied by a photo of a bearded and beaming Dr. Michael Keating, who also looked full of experience and reassurance, reported that a new combination of rituximab, fludarabine, and cyclophosphamide (RFC) had a 69% “complete response” rate in previously untreated patients. (Eventually, patient reader, I will post in detail about “complete” and other responses in CLL; as usual with this disease, things are never as they seem.)

fore I stumbled across an interesting treatment prospect, outlined in the Spring 2003 Leukemia Insights newsletter from the MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. The article, accompanied by a photo of a bearded and beaming Dr. Michael Keating, who also looked full of experience and reassurance, reported that a new combination of rituximab, fludarabine, and cyclophosphamide (RFC) had a 69% “complete response” rate in previously untreated patients. (Eventually, patient reader, I will post in detail about “complete” and other responses in CLL; as usual with this disease, things are never as they seem.)

If I had to do chemo, RFC made better sense than fludarabine alone, which had a much lower response rate. Indeed, the very important fact that there was only a 20 percent chance that fludarabine would provide me with a “complete response” had been ignored by both my doctor and Berlex. When my doctor called to ask me what I had decided, I told her about RFC, which seemed to me to be a promising discovery.

“Oh, that,” she said. “I tried that with someone and he ended up in the hospital on a ventilator.”

Oops.

“Let me think about this some more,” I said. “I’ll get back to you.”

No easy choices

The more Marilyn learned about the side effects of chemo, the more she threatened to break my kneecaps if I ever decided to leave the house for treatment. Indeed, the evidence began to mount that some side effects could in themselves be life threatening. I realized that there were some unlucky people who were, evidently, done in by their treatment. Remissions were followed by fatal secondary cancers, bone marrow was so compromised that it became “dead” and the patient had no immune system left. Simple infections could then prove fatal.Some time later we learned that fludarabine has been shown to give a free pass -- at your expense -- to the worst type of CLL cell, the one with the 17p deletion. Bear with me for a minute, if you're interested in further proof of the theory of evolution: CLL cells are wonky little buggers, deformed as a result of chromosomal abnormalities, some of which doctors have recently become familiar with. There is a test called FISH (Flouresence In-Situ Hybridization) that checks for the more common abnormalities. The worst of them is what’s called the 17p deletion, which carries with it a much shorter median survival for the patient than any other prognostic indicator in CLL.

In a normal situation, thanks to a functioning “TP53”gene -- where the 17p is located -- cells have a mechanism by which they can tell themselves to die. This death is called "apoptosis" (or perhaps "Apophis," for confused Stargate SG-1 fans). Every CLL patient most likely has a few B cells with this deletion or that, including 17p. (The FISH test only puts up the red flag when a high percentage of cells tested show a particular deletion, about 20% being the problem point for 17p.) A few out of billions isn't going to matter, usually, since they all compete to survive, often preventing the worst one from predominating. So along comes fludarabine, which relies on the 17p function to do its job, to tell the cell to die. It kills off those CLL clones with functioning 17p. And what doesn’t it kill? The ones where the 17p is deleted, the very worst ones of all. The other clones having been eliminated, the bad boys now have the field – your body – to themselves. Very Darwinian.

This danger is mitigated somewhat by adding other agents that don't rely on 17p, s uch as rituximab, to fludarabine therapy. Indeed, there is a more-is-better school of thought when it comes to chemo, if you can get past the potentially life-threatening toxicities. But those should not be taken lightly, especially if your back isn't to the wall. It now appears, for example, that the use of fludarabine and immunosuppressive combination therapies such as RFC may be implicated in the overall rise in cases of Richter’s Transformation; this is where the disease takes a nasty turn into large cell lymphoma, and the median survival time is less than a year.

uch as rituximab, to fludarabine therapy. Indeed, there is a more-is-better school of thought when it comes to chemo, if you can get past the potentially life-threatening toxicities. But those should not be taken lightly, especially if your back isn't to the wall. It now appears, for example, that the use of fludarabine and immunosuppressive combination therapies such as RFC may be implicated in the overall rise in cases of Richter’s Transformation; this is where the disease takes a nasty turn into large cell lymphoma, and the median survival time is less than a year.

I had to weigh the choices: If there was a chemo regimen that could guarantee a cure, or at least a very good chance of one, it might be worth taking the risks. But there’s a reason it’s called a chronic disease: chemo can delay it but it cannot stop it. And while there certainly are cases where aggressive chemotherapy is absolutely justified, I had to wonder if mine was one of them. Remember, the main reason for treatment at all was "cutting off a kidney." The only prognostic test I could get at that time -- just two years ago but eons past in terms of available prognostics -- was CD 38, which showed me at 12%, and therefore "negative," and therefore ostensibly with less aggressive CLL.

Still, if I needed treatment, then I had to do something. So we continued our research, trying to absorb as many big words and new concepts as we could while my oncologist fidgeted nervously in the background, visions of exploding kidneys dancing in her head. As it turned out, the more we looked into things, the more we learned that my doctor’s concern about the kidney was highly unusual. We began to suspect that despite charging more than $400 per 10-minute visit, we might not be getting our money’s worth, or our insurance company’s money’s worth, when it came to her CLL expertise.

The worst word in the English language

Meanwhile, we ran across something else to be concerned about, a simple word that Berlex failed to mention anywhere and that my doctor had also avoided: refractory.

"Refractory" is my least favorite word, and that’s quite an accolade, since there are so many to choose from. Removing the side effects issue from the discussion for a moment, if chemotherapy was guaranteed to work every couple of years ad infinitum, then we’d already be at the point where CLL is a controlled disease. But one of the problems is that nothing works forever. Patients can become refractory to a drug, which means the drug won’t work on them anymore. Almost everyone becomes refractory to fludarabine, for example.

This came as a rude shock, something that drug companies and doctors don’t really like to discuss and that patients don’t like to hear. The guy that Dr. Lippencot said had been on fludarabine for “ten years and going strong” was probably skating on very thin ice at this point.

Out of this discovery about “refractory” came some crystal clear logic that began to guide my treatment decision:

Use a drug today when you don’t need to, and that’s one less time you can use it in the future. You only get so many chances with the various drugs that are available, and you’ll likely have no idea how many chances you’ll get with any given one. Don’t burn any bridges before it is wise –- or at least unavoidable -- to do so.

Google does good

One night I decided to investigate this rituximab stuff (trade name Rituxan) that had been so instrumental in the apparent success of the RFC protocol at MD Anderson. I did a Google search and ran across CLL Topics for the first time. Suddenly another side of the story came into view: Rituxan as a single agent, or "monotherapy." Here was this retired chemist named Chaya Venkat, who was reinventing the wheel in an effort to save her husband’s life, saying things like, “Be smart in making your therapy decisions, play for time and stay as healthy as possible in the meanwhile. Live to fight another day when the odds are even more in your favor.”

That made sense.

It was also heartening to see that someone out there with absolutely no vested interest in the cancer business had begun to intelligently deal with all the issues that Marilyn and I had been wondering about: toxicity, effectiveness, what to do and when to start, what tests to have and how to get a handle on where my disease really stood.

As I perused Topics I began to get a better grasp of the science, and I saw a little l ight in the darkness: Rituximab is a monoclonal antibody (thus the "mab" in the name) created from mouse cells. It is designed to bind to the CD 20 receptors on human B cells, and cre

ight in the darkness: Rituximab is a monoclonal antibody (thus the "mab" in the name) created from mouse cells. It is designed to bind to the CD 20 receptors on human B cells, and creates

an antigen-antibody complex that signals to the body's immune system that we are being invaded and need to fight back. The body -- through such things as neutrophils, NK cells, macrophages, and a mysterious soup called complement -- assists the Rituxan in the cell kill. There are few downsides for most people, usually the worst being that Rituxan also tags normal B cells as well. CLL patients still have a few of them, and their function is important, so one is left with some immune weakness during and after Rituxan therapy, though this pales in comparison to what chemo drugs do.

Rituxan works well in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, where CD 20 levels are usually over the top, and I read on Topics that it also seemed to work fairly well on some CLL patients, especially those with highly-expressed CD 20. Excited about the prospect of finding a treatment that would possibly control my CLL with minimal side effects, I went immediately to the file cabinet and pulled out my medical records. I knew I had been tested for CD-this and CD-that. And there it was, CD 20: Moderately bright, expressed on 92 percent of cells.

I was a good candidate for Rituxan monotherapy. There was a way out. (And for those of you who, on the surface, may not be such good candidates, don’t get discouraged. It seems to work pretty well in some people with “dim’ CD 20, too.)

Jumping the SS Lippencot

On my next visit to Dr. Lippencot, I discovered that she was actually afraid of Rituxan. She didn’t want to use it, either alone or in combination with anything else. It might, she asserted, "crum up" my kidneys. Indeed, in the very early days of Rituxan's use in CLL, doctors sometimes did not anticipate the high degree of tumor lysis, or cell die-off, that would result. This did lead to kidney problems in a few patients. But with adequate precautions -- taking allopurinol, drinking a lot of water, slower infusions over more days, even leukepheresis -- this is now a dead issue, and should have been in late 2003, also. I had to wonder, following the ventilator story she had told me, whether another CLL patient was now on dialysis somewhere following her administration of Rituxan.

Finally, Lippencot resorted to pulling out tricks at random. My insurance, she claimed, might not pay for Rituxan (not that she'd asked them, and she was wrong). Reservations about chemotherapy are the products of "fear-based thinking," so I was a misguided wuss. Fludarabine, in her experience, "works repeatedly." Noticing my lazy right eye, she posited that it could be the result of CLL getting into my central nervous system (highly unusual, by the way). Finally, she exclaimed, "I've been doing this for a lot of years!"

What I learned was that she had her comfort zone, which started with chlorambucil and ended with fludarabine. Her self-limitations were limiting my choices, and compromising my medical care. Ultimately, she could do little for me.

Sensing that my balkiness would not be easily overcome, she had me see her new partner, an oncologist whom, she volunteered, "has had a lot of experience with CLL." It was his first day at work, and he did what any good business partner does: stood by her decision tooth and nail.

Our conversation started badly and then devolved. He spat out various acronyms of older therapies that he was familiar with -- CHOP and COP and so on -- and ended up by insisting that fludarabine w as "all you need." Rituxan, comparatively mild and already demonstrated to add enormously to the effectiveness of fludarabine therapy, was out of the question. When I mentioned using Rituxan by itself, I may as well have been yelling "The power of Christ be upon you" at a demon-possessed child. “Rituxan is not standard therapy for CLL!” he repeated at least three times, his voice growing more shrill and his face growing redder. If he could have rotated his head 360 degrees while spewing green slime, he probably would have done so.

as "all you need." Rituxan, comparatively mild and already demonstrated to add enormously to the effectiveness of fludarabine therapy, was out of the question. When I mentioned using Rituxan by itself, I may as well have been yelling "The power of Christ be upon you" at a demon-possessed child. “Rituxan is not standard therapy for CLL!” he repeated at least three times, his voice growing more shrill and his face growing redder. If he could have rotated his head 360 degrees while spewing green slime, he probably would have done so.

Finally, like my Jewish grandmother, he ended up warning: “You could end up in the ER here with kidney failure! Is that what you want to happen?”

Armed with the power of information, Marilyn and I knew that it wasn’t going to happen, and we knew this would be our last visit to this office. On the way out we passed the pleasant infusion room with the spectacular view. It had now taken on an almost sinister aura, and we were glad to be done with the place.

A room without a view

Through patient networking I managed to find an open-minded oncologist a couple of hours away. She was younger, down to earth, pleasant but hardly the touchy-feely type. Lippencot had initially exuded an enveloping sense of calm, until my kidneys got the best of her; my new doctor was pretty much all business. I realized that bedside manner is not the end point of treatment, and I was grateful to have found someone familiar with recent advances in CLL therapy.

The new doctor was open to RFC, and I considered it. It was then, and is now, a new treatment, its track record being written as we speak. There was no way of knowing how long a remission might last, assuming I had no nasty complications. Even a best case scenario -- maybe five years? -- didn't answer that eternally nagging question in CLL therapy: Then what? So I opted for the less dramatic but safer and to me more logical choice: Rituxan alone. RFC, or the next generation of combination chemo, would always be there if I needed it.

We decided to proceed with Rituxan sooner rather than later because my disease had progressed to the point that Rituxan’s effectiveness might be significantly diminished if I waited much longer. The more impacted lymph nodes, and the bigger they are, the harder it is for Rituxan to get into them and do the job.

It was a fine line to walk, of course. I had possibly set the clock ticking on Rituxan’s usefulness in my case, though the jury is still out on if, and to what degree, CLL patients become refractory to it. But I did not want to let my disease get to the point where I would have no choice but to use something more heavy-duty. I was playing for time and it was a calculated risk, which is the name of the game in CLL.

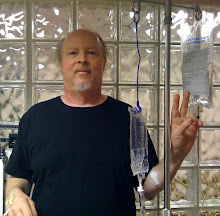

My new doctor’s infusion room was about as inspiring as a bus station, but I didn’t mind. After the first infusion, my absolute lymphocyte count dropped from 157,000 to 9,900. The second week saw my spleen empty out. By the time I was done with eight rounds of Rituxan, my lymphocyte count was down to 2,300. My spleen appeared to be normal, and most lymph nodes were as well. It hadn’t been so effective on a few, and I knew going in that Rituxan doesn’t clean out the marrow like some of the tougher chemo regimens do. But it also doesn’t have the long-term negative effects, and I had not engaged in any significant bridge-burning.

I felt, as I left the office following my last treatment, that I had done the right thing. Everyone in life has their regrets; I am glad that when it came to this life-and-death matter, I had none.

Epilogue

A year and a half later, when the IgVH mutational status test became widely available through Quest Diagnostics, I found out that my decision to avoid single-agent fludarabine was a good one for another reason: I am unmutated, in that unfortunate group whose CLL tends to reproduce more quickly. But I also have a “normal” FISH result, with no deletions in crucial chromosomes such as 17p and 11q, and this has probably kept the disease reasonably well-behaved up to now. Had I followed Lippencot's advice and used fludarabine alone, there is a decent chance that it might have selected for CLL cells with the worst deletion possible – 17p – leaving me with a recipe for the worst form of CLL: a bad karotype and unmutated. And likely a lot less time on the planet.

I also discovered after the fact that Dr. Lippencot had been pushing fludarabine knowing full well that a blood test had shown that I was "Coombs positive." This means I have developed antibodies to my own red blood cells, not a pleasant thought, and therefore am more prone than average to develop a full-blown case of autoimmune hemolytic anemia, or AIHA, which is no walk in the park. Even the cartoon booklet published by Berlex mentioned this one. The Mayo Clinic, in its latest standards and practices of care, cautions against the use of fludarabine in such patients, as fludarabine can trigger AIHA. Even though I was no longer Lippencot's patient, I dropped a copy of the Mayo article off at her office, hoping against hope that she might, through some miracle that would rival the parting of the Red Sea, absorb the information.

RESOURCES

For more about the current state of CLL treatment, and for some very interesting comments on fludarabine refractory patients – and that means you, eventually, if you use it – read this article by the highly-respected Dr. John Byrd and others: http://www.asheducationbook.org/cgi/content/full/2004/1/163

You can read about the Mayo Clinic's "Current Approach to Diagnosis and Management of CLL" at: http://tinyurl.com/dvk23

For more about prognostic testing, such as the IgVH mutational status and FISH tests referenced above, check out this link at CLL Topics, which also contains links to other articles about prognostics: http://tinyurl.com/cog3e

Vis-a-vis the question of immunosuppressive therapy and Richter's Transformation, there is an abstract here: http://tinyurl.com/b9c5x

I will post more about the pluses and minuses of single-therapy Rituxan, as well as combination chemotherapy (there is an interesting and important debate over RFC). Figuring out what kind of CLL you have, and what to do about it, is the main task that patients face.

And, yes, Lynn Lippencot is not her real name.

be, by and large, friendly and accommodating. Traveling on a frayed shoestring of a budget, we stayed at such places as the Grand Hotel de La Loire in Paris, which was anything but grand –- the hotel, I mean. Paris was wonderful –- romantic, beautiful, exemplary in every way but for the dog poop that littered the streets -- and our eyes still tear up at the thought of an artichoke in hollandaise sauce that we had at a café on the Ile St. Louis.

be, by and large, friendly and accommodating. Traveling on a frayed shoestring of a budget, we stayed at such places as the Grand Hotel de La Loire in Paris, which was anything but grand –- the hotel, I mean. Paris was wonderful –- romantic, beautiful, exemplary in every way but for the dog poop that littered the streets -- and our eyes still tear up at the thought of an artichoke in hollandaise sauce that we had at a café on the Ile St. Louis.