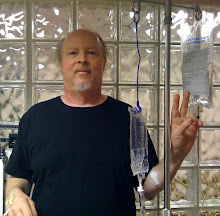

Now that I'm 50, I suppose I need to start worrying about um, er, what was it? Oh, senior moments.Having chronic lymphocytic leukemia, I have another strike against me: the prospect of getting "chemo brain" from heavy-duty chemotherapy, should it ever become necessary. This is one of the hidden dangers of CLL and most cancer therapy, and yet another reason to avoid the alphabet soup treatments such as RFC. RFC+M, CFAR, et al until you have no choice and really need to use them.Researchers tend to talk about "multiple non-overlapping toxicities" and doctors tend to use phrases like "well-toler ated" when describing some of these regimens. (I suppose whatever doesn't kill you is something that, grading on a curve, you can tolerate well.) But in plain old common sense English, pump your body full of stuff that destroys cells and don't be surprised if it does something in the brain.Of course, chemo brain is one of those areas that is not really the subject of too many studies. After all, drug companies have little incentive to reveal yet another potential problem with their products. And researchers looking for a cure or effective control may feel their time is better spent on that rather than on tracking down amorphous side effects that can vary from person to person. Type "chemo brain" in quotes into PubMed and you get exactly three results (though there are other areas which better catalog the information available -- see "Resources" below).It is on internet CLL patient forums that one hears stories about chemo brain: people becoming disoriented and not knowing where they're going when they're driving down the street, people who go to work and can no longer answer the phone and type into the computer at the same time. Some people seem to be spared these sort of effects, some have mild or transient cases, some have long-term problems.

ated" when describing some of these regimens. (I suppose whatever doesn't kill you is something that, grading on a curve, you can tolerate well.) But in plain old common sense English, pump your body full of stuff that destroys cells and don't be surprised if it does something in the brain.Of course, chemo brain is one of those areas that is not really the subject of too many studies. After all, drug companies have little incentive to reveal yet another potential problem with their products. And researchers looking for a cure or effective control may feel their time is better spent on that rather than on tracking down amorphous side effects that can vary from person to person. Type "chemo brain" in quotes into PubMed and you get exactly three results (though there are other areas which better catalog the information available -- see "Resources" below).It is on internet CLL patient forums that one hears stories about chemo brain: people becoming disoriented and not knowing where they're going when they're driving down the street, people who go to work and can no longer answer the phone and type into the computer at the same time. Some people seem to be spared these sort of effects, some have mild or transient cases, some have long-term problems.

Depression complicates matters

Chemo brain is a very real risk, though matters of depression and stress can lead to an impression of brain fog in some people that may not be entirely chemo-related.A PubMed abstract of a 2003 study at the University of Indianapolis provides this analysis: "Oncology patients often complain that their "mind does not seem to be clear." This subjective perception, sometimes referred to as "chemo brain," may be due to situational stressors, psychological disorders, organic factors, or effects of neurotoxic medicati ons. Cognitive decline cannot only diminish quality of life, but can also interfere with a patient's ability to make decisions regarding complex treatment issues."The authors of the study tried to quantify and clarify the results in 61 patients. They found this to be difficult, and concluded: "While the perception of cognitive impairment is common in cancer patients, there may be problems in interpreting the nature of these complaints, particularly in separating them from depressive preoccupation."Certainly depression can lead to reduced clarity of thought and action. Many older people have CLL and may already be experiencing a bit of brain slowdown as part of the natural aging process. But chemo brain cannot be dismissed as a figment of the imagination. A study reported today by UCLA researchers finally pins down in hard science what many cancer patients have felt to be true all along.

ons. Cognitive decline cannot only diminish quality of life, but can also interfere with a patient's ability to make decisions regarding complex treatment issues."The authors of the study tried to quantify and clarify the results in 61 patients. They found this to be difficult, and concluded: "While the perception of cognitive impairment is common in cancer patients, there may be problems in interpreting the nature of these complaints, particularly in separating them from depressive preoccupation."Certainly depression can lead to reduced clarity of thought and action. Many older people have CLL and may already be experiencing a bit of brain slowdown as part of the natural aging process. But chemo brain cannot be dismissed as a figment of the imagination. A study reported today by UCLA researchers finally pins down in hard science what many cancer patients have felt to be true all along.

New study: chemo alters brain metabolism

Entitled "Chemo has long-term impact on brain function: study," Reuters reported the following:Chemotherapy causes changes in the brain's metabolism and blood flow that can last as long as 10 years, a discovery that may explain the mental fog and confusion that affect many cancer survivors, researchers said on Thursday. The researchers, from the University of California, Los Angeles, found that women who had undergone chemotherapy five to 10 years earlier had lower metabolism in a key region of the frontal cortex. Women treated with chemotherapy also showed a spike in blood flow to the frontal cortex and cerebellum while performing memory tests, indicating a rapid jump in activity level, the researchers said in a statement about their study.

"The same area of the frontal lobe that showed lower resting metabolism displayed a substantial leap in activity when the patients were performing the memory exercise," said Daniel Silverman, the UCLA associate professor who led the study. "In effect, these women's brains were working harder than the control subjects' to recall the same information," he said in a statement.

Experts estimate at least 25 percent of chemotherapy patients are affected by symptoms of confusion, so-called chemo brain, and a recent study by the University of Minnesota reported an 82 percent rate, the statement said.

"People with 'chemo brain' often can't focus, remember things or multitask the way they did before chemotherapy," Silverman said. "Our study demonstrates for the first time that patients suffering from these cognitive symptoms have specific alterations in brain metabolism."

The article goes on, and this link will take you to the full text.But the message is simple: chemo brain is real, and it is a risk. Yes, there have been no studies of it in CLL, but there is more than ample anecdotal evidence that some people are affected by it. For those of you who feel your body is crumbling but "at least I have my mind," take heed.

RESOURCES

The website http://www.chemobraininfo.org/ offers a fairly encyclopedic roundup of studies and other information.

also caught by my brother after the gathering ended.

also caught by my brother after the gathering ended. of flying, when they actually cleaned the planes between uses, right down to replacing the paper things that were hung over the top of the headrests for sanitary reasons. You could fit into the seats, and they gave you three meal choices in coach. Things have now deteriorated to the point that I would not be surprised to see people boarding with babushkas and chickens. But I digress.

of flying, when they actually cleaned the planes between uses, right down to replacing the paper things that were hung over the top of the headrests for sanitary reasons. You could fit into the seats, and they gave you three meal choices in coach. Things have now deteriorated to the point that I would not be surprised to see people boarding with babushkas and chickens. But I digress.