The room, as it were, has not stopped spinning since.

I was going to title this post “Six years of this crap,” but I think it’s best to look back with a more even temperament at some of the big screaming bullet points that I have run across. These are things that may be the most help to those of you who are waking up into your own CLL bad dreams.

Since 2003 I have come some distance in my understanding of the disease and what it means to cope with it. Ti

me is a teacher, and I’m sure it has a lot more to throw my way — at least I hope it does, if you catch my drift. At six years in, I’m in my CLL middle age, both in terms of disease progression and knowledge. When it comes to the latter, I'm no longer wet behind the ears, yet wise enough to know that the learning curve goes on forever.

me is a teacher, and I’m sure it has a lot more to throw my way — at least I hope it does, if you catch my drift. At six years in, I’m in my CLL middle age, both in terms of disease progression and knowledge. When it comes to the latter, I'm no longer wet behind the ears, yet wise enough to know that the learning curve goes on forever.Here are some things I’ve learned, sometimes the hard way. They may represent a change or an evolution in thinking over some older posts in the blog. They are the truth as I see it today:

1. CLL is not the same disease for everyone. The “CLL is an indolent disease/good cancer” monster has to be staked through the heart every time it gets out of its coffin to suck your blood. It is the old, cobwebby way of thinking about CLL. Wipe those cobwebs from your eyes, unless you enjoy being mesmerized while your life drains away.

Some of us have relatively mild CLL, some of us don’t. Some of us respond really, really well to easy, breezy treatments, and others of us barely respond to nuclear chemo. This is because, for all practical purposes, we don’t have the same disease. A dog is a dog is a dog, but not all dogs are alike: Paris Hilton would look a lot more chewed up if she were carrying around a pit bull instead of a chihuahua.

Figuring out what kind of CLL you have does not involve reading tea leaves, poring over entrails, or consulting the shell of the prescient tortoise. It’s a matter of looking at the results of the tests available — IgVH mutational status, ZAP-70, FISH, CD38 — and at your clinical history (how fast your nodes are growing, how quickly your lymphocyte count is doubling, how far your hemoglobin and platelets are dropping). When I was diagnosed, the only readily-available test was CD38, so a lot has happened in six years. If you want to know what you’re dealing with, get your tests done.

2. See a a CLL expert (or two) at the very outset. Ol’ Doc Lippencot, highly regarded as she is around these parts for curin’ breast cancer and lice and possum infestations and such, didn’t know much about CLL. This is often the case with the local doctor, whose stock in trade is usually not going to be a disease that affects almost nobody.

And while patient networks and educational websites are excellent for moral support, learning about case histories, and keeping up with the latest research news, they are of limited medical expertise. This is because they are filled with seekers and guessers such as yourself, not to mention the occasional insufferable blowhard. Some of these people are downright brilliant, some of them are extraordinarily helpful. But in the final analysis they are, like yours truly, amateurs — what the dictionary defines as “lacking the skill of a professional.”

Which brings us to the professionals. Experts live and breathe CLL and have seen hundreds of people just like you, with all the variants of your disease. They have a clue. This does not make them infallible. Having consulted a few, I can say that they don’t always agree. Just as painters see the world differently, so do those who practice the art of medicine. So see a couple of the big names — or even a few, the worse your case is — just to get a consensus, or maybe that much more confused.

Our CLL experts are a great bunch — many of them are approachable by e-mail — but they’re not miracle workers and they’re not gods. Sometimes they run out of things they can do to save your life. Dr. Terry Hamblin told me in an e-mail once that, the way things stand today, doctors can only keep me alive for so long. I forgot how long “so” was — it appears to be at least six years — but the point was well taken, which leads me to:

3. The battle has a beginning and an end, and you need to be ready to fight. For those of us who don’t have indolent “goody-two-shoes” cancer, the day will come when we beat it or are beaten by it. The opening round came when that first mutant CLL clone got out of your own personal Pandora’s Box. The final round will come when it comes, and for many of us younger patients it will probably end with a transplant, win or lose (or there can even be a draw, of sorts).

Obviously, you need to be as prepared as possible. That is why patient education is important, getting the lay of the land is important, staying up with truly useful news is important, staggering your treatments intelligently is important, doing all the strategy and tactics stuff is important.

And that is also why learning to cope emotionally is important, and why this battle hinges at its heart on more than science and medicine. Healing is a big, mysterious thing. Books have been written. Bullshit has been blathered. But there is a lot about the mind-body connection that we don’t understand. Well-respected, level-headed doctors see “medical miracles” during their years of practice. I believe your chances of healing are better if you put your heart and soul into it, and

the evidence seems to back me up.

the evidence seems to back me up.Emotional preparedness can also help you cope with the inevitable surprises and slip-ups, the disruptions and disappointments (and occasional triumphs) that come with fighting cancer. It is a rough journey, a test of your faith and your stamina, something that demands that you get your inward act together.

You can walk out into the ring with all the technical skills, having read hundreds of papers and abstracts, having consulted every expert doctor within a ten thousand mile radius — but if you don’t learn to float like a butterfly and sting like a bee, if you can’t get in your groove, make knowledge and soul work together, you are fighting with one hand tied behind your back.

4. Be a pain in the ass. No, I don’t mean be a cry-baby or a whiner or a ninny (take that blood draw like an adult!). I mean learn to stand up for yourself in medical settings, learn to question things if you are uncomfortable, learn to say “No” and “Are you sure?” Do not be railroaded by doctors, office staff, or well-meaning family or friends. Be as diplomatic as the situation allows, but keep in mind the words of Teddy Roosevelt: “Speak softly and carry a big stick.”

This is where those emotional/intuitive clues come in handy. If someone says, “This is right,” but it doesn’t feel right, honor that thought. Float like a butterfly, and whack! with that stick. And the bigger the thing, the bigger the pain you must be. Do not stand on ceremony or save face; it will be at your own peril. The face you save could be you own.

5. You cannot predict the future with certainty. So far, CLL has humbled the great minds of medicine, so get your humble on. Nobody can predict the future. Nobody can know an outcome for certain. Sure, a lot of cases follow the conventional wisdom; things often, unfortunately, go by the book.

But there are exceptions. Let me tell you a story:

A patient has a sudden relapse, finds herself refractory to every therapy, has to live on transfusions. Like a Greek chorus, there is whispering offstage: “She should go into hospice.”

And now, two years later, like some mighty Greek goddess who has triumphed in an epic battle, she has survived a sudden transplant and is doing pretty well, thank you.

Bad things often happen in CLL, but good things can, too. This is not an article of

faith, it is a matter of medical fact. There really IS hope, tempered as it is by this thought:

faith, it is a matter of medical fact. There really IS hope, tempered as it is by this thought:6. In the end, it often comes down to luck. Dr. Allan Hamilton is a respected neurosurgeon, and the author of a book called The Scalpel and The Soul, and his number one piece of advice after decades of practice is this: “Never underestimate luck — good or bad.”

The more I see of CLL, the more I believe this to be true.

Why do some people live and some die? My ever-practical younger brother puts it this way: “When your number’s up, your number’s up.”

It’s called Fate. This is why the best-prepared sometimes fail, why the least-prepared sometimes live. That’s no reason not to care, no reason not to make the odds as much in your favor as you think you can make them.

But nobody gets off this planet alive. Dr. Hamilton has a blog, and he talks rather poignantly (tearjerker alert) about a couple who drive up a mountain to share a glass of wine in the twilight of life.

So enjoy wine and a sunset, whatever day it is for you. Life is not all about the battles we wage to stay here. It is about how we live it while we are blessed to be here.

That can be easy to forget when you’re in the trenches battling cancer. But with time and wisdom, we can learn to savor what life is about despite the challenge it has thrown at us. And life can become all the more sweet in the face of the dangers ahead.

Nobody said beating CLL was going to be easy, but nobody who knows what they’re talking about says it can’t be done.

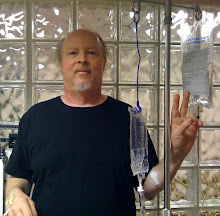

So here’s to six more years (come to think of it, I think the number “12" was in Dr. H’s e-mail somewhere).

With this post, I am stepping back from the blog for awhile. I have some fighting trim to get into. There are other things in life I must attend to. Over the years I have said a lot, but sometimes there is wisdom in being quiet and listening. I promise to post every few months, and I will let you know if I encounter any big health emergencies or breakthroughs. In the meantime, no news is good news. Take care, and stay as healthy as you can.