skip to main |

skip to sidebar

I had an interesting reply to my last post, Opportunity Cost, Opportunity Lost. Written by “Anonymous,” that John/Jane Doe of the internet, it went:

“Dr. Hamblin disagrees with you. He has written in January 2006 (search his blog) that the patient should have his spleen removed, have transfusions, just about be on his deathbed before starting treatment. Read his blog entry if you don't believe it.”

I follow Dr. Terry Hamblin’s blog, and I have read the entry in question, as well has his other entries on the subject, and I generally agree with his approach to treatment. In fact, one of the most important things he has done through his blog and his participation in the ACOR list has been to raise patient awareness about the limits of treatment, and to argue effectively that it should usually be the last resort, not the first.

Anonymous is assuming incorrectly that the purpose of my last post was to promote early treatment; it was merely to show that there can be opportunity costs associated with treatment decisions, including ones in which we avoid treatment at all costs (pun intended).

If we didn't have any soft-glove treatments for chronic lymphocytic leukemia -- which was the case until a few years ago -- I would probably agree with what Anonymous said Dr. Hamblin said. I would have to be at least half dead, preferably three-quarters, before starting treatment.

Of course, it is easy to say something like that, and another thing to do it. Take a splenectomy, for example. Removing a huge spleen involves major surgery, and doing it in a patient whose marrow has crashed to the point of needing transfusions makes it a much more dangerous operation than it would be in an earlier-stage patient. Is there not an opportunity cost if this hypothetical patient succumbs to operation complications or a hospital-related infection by having waited too long to deal with the spleen?

These irksome opportunity costs are lurking everywhere we CLLers turn, and they are to be ignored at our own peril. Explaining this concept was the purpose of my last post, and elaborating on it is the purpose of this one.

Float like a butterfly

Back to the point about soft-glove treatments. In 2006, we do have one -- the CD20 monoclonal antibody Rituxan (rituximab), which is likely to be followed soon by HuMax-CD20 (ofatumumab), which is now accruing patients for Phase III trials and has been accorded fast-track status by the FDA.

(Chaya Venkat of CLL Topics has written a few tantalizing lines about an even more powerful monoclonal coming down the pike, nicknamed the “B1 bomber.” And there are, of course, researchers hither and yon working on some interesting concepts such as HSP-90 inhibitors and treatments to attack the ZAP-70 protein. All of these targeted therapies -- some of which won’t pan out, and some of which will -- promise much lower toxicity than traditional chemo.)

are, of course, researchers hither and yon working on some interesting concepts such as HSP-90 inhibitors and treatments to attack the ZAP-70 protein. All of these targeted therapies -- some of which won’t pan out, and some of which will -- promise much lower toxicity than traditional chemo.)

In some patients and under some circumstances, these low-tox therapies can change the game. I view these drugs as tools -- methods, essentially, of extending watch and wait. (Or, put another way, methods of disease control, however imperfect.) While they don't come with no cost, the risk-reward scale tends to put them into a different category from traditional treatment.

To quote Dr. Hamblin, from his blog entry referenced above:

“If treatment is inevitable, my choice would be the treatment that is least harmful. At the moment this is rituximab. It only works in about half the patients, and it does lower the levels of normal B cells, but this is transient and they quickly return. Rituximab plus a growth factor like G-CSF or GM-CSF may well be more effective. So if it works for you and gives you a year off treatment then go for it, and don’t be afraid to repeat it. True rituximab resistance is very rare. In some patients increasing the dose will turn a non-responder into a responder.”

Building bridges and blowing them up

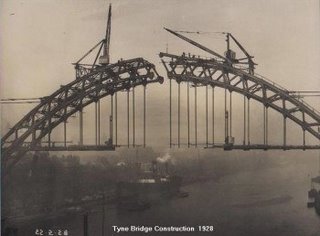

Rituxan and the coming next generation of monoclonals mean that patients may be able to build bridges into the future while still preserving hard-chemo options should they become necessary. If one can scrape by with Rituxan until HuMax arrives, then scrape by with that until the B-1 bomber takes the field, or until a monoclonal targeting something else becomes available, or until a breakthrough in vaccine or molecular or biologic therapy happens, one has made a wise use of these opportunities.

scrape by with Rituxan until HuMax arrives, then scrape by with that until the B-1 bomber takes the field, or until a monoclonal targeting something else becomes available, or until a breakthrough in vaccine or molecular or biologic therapy happens, one has made a wise use of these opportunities.

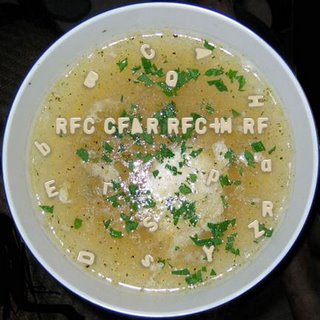

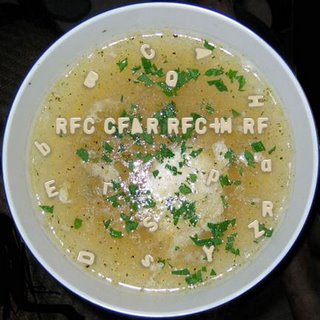

Conversely, if one hits the CLL hard at the start with what I like to call Alphabet Soup Chemo -- RF, RFC, CFAR, RFC+M, R-CHOP and the like -- one has paid a big price in terms of opportunity cost: The soft-glove drugs work best in people whose immune systems are relatively intact, and Alphabet Soup Chemo can lead to all sorts of immune problems, including neutropenia, T cell depletion, and such nasties as myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS). While CFAR is blasting away at your CLL, it is also burning your soft-glove bridges.

That said, drug response in CLL -- depth of remission, tolerance and side effects, development of disease resistance -- can be idiosyncratic and unpredictable. Rituxan is no panacea, and for some it is pretty much a wasted effort.

For others, it is a lifeline, allowing them to maintain a good quality of life for a long time. I am a Bucket C case, and my disease has progressed a bit despite my three courses of Rituxan. But I believe that Rituxan has slowed that progress. (In the irony department, is “progress” really the right concept here?) I am IgVH unmutated, now with the 11q deletion, and I have been at Stage 2 since my diagnosis three years ago. Would I have progressed by now to a later stage without the Rituxan? There is no way to know for sure, but I decided long ago that the opportunity cost of doing nothing was too great to risk finding out.

Single-agent Rituxan is not, of course, an acceptable approach to some doctors. (Among these, it seems, are a few like Lt. Col. Bill Kilgore of Apocalypse Now, who love the smell of napalm in the morning.) They would argue that there is an opportunity cost to using soft-glove treatments prematurely, that this use may render them less effective in combination therapy when and if the time comes that a patient needs a stellar, MRD-negative remission.

From what I gather, though, patients using Rituxan as a single agent do not close the door on this; the synergy between Rituxan and chemo agents seems to boost the effectiveness of both, though there may indeed be some diminution. The patient is left looking at opportunity costs and wondering: Do I let the disease go until I might need Alphabet Soup Chemo, reserving my Rituxan for the best possible remission then? Or do I try to control the d isease with it now -- perhaps putting off that Alphabet Soup Chemo forever if I build my bridges right -- yet knowing that my chances of a MRD-negative remission may be somewhat reduced if I ever need one? (And, let’s add these delightful monkey wrenches: Do I assume that science will/will not come up with additional drugs that might render these costs moot in X number of years? Is a MRD-negative remission all it’s cracked up to be?)

isease with it now -- perhaps putting off that Alphabet Soup Chemo forever if I build my bridges right -- yet knowing that my chances of a MRD-negative remission may be somewhat reduced if I ever need one? (And, let’s add these delightful monkey wrenches: Do I assume that science will/will not come up with additional drugs that might render these costs moot in X number of years? Is a MRD-negative remission all it’s cracked up to be?)

So far -- and again, this is my personal view -- I can only see three cases where enduring the toxicities and potentially deadly complications of Alphabet Soup Chemo is worth it:

One is in a pre-transplant situation, where extreme cytoreduction is a key to success.

The second is in cases where a person’s disease is past the point of being controlled by soft-glove treatments, or by palliative means such as transfusions, and in which the benefits of Alphabet Soup Chemo decisively outweigh the risks.

The 17p dilemma (and a bit of good news)

The third, perhaps -- and this is a big “perhaps” -- is in the case of early-stage, high-risk patients. In fact, there is some debate among experts about whether early intervention may be warranted in patients with the worst cytogenetics, such as unmutated, 17p-deleted cases. In a newly-diagnosed, asymptomatic, Stage 0 patient with unmutated 17p (or even 11q) CLL, is there an opportunity cost to doing nothing? After all, the disease always progresses, fewer drugs work on 17p, and both 17p and 11q patients tend to get shorter-duration remissions. Is it better for the patient to pull out the alphabet soup and blast the disease early, go for something of a cure?

Of course, this being CLL, there is always another way of looking at things.

Here’s an interesting tidbit from a pilot study of 12 patients by Ron Taylor and company at the University of Virginia. Taylor is a leading proponent of the concept of CD20 “shaving,” and suggests that low-dose Rituxan may actually be more effective than higher-dose given the way the body’s complement system responds to the drug. The study included six patients with the 17p deletion. Patients were given either 20mg/m2 or 60mg/m2 of Rituxan three times a week for four weeks (the usual dose is 375mg/m2, so this is really low dose.) The results flew in the face of conventional wisdom, which is that Rituxan doesn’t work in 17p cases: “The two patients with the highest cell surface CD20 expression achieved CR (complete response),” the authors wrote, “despite the presence of the del 17p in both cases.”

of Virginia. Taylor is a leading proponent of the concept of CD20 “shaving,” and suggests that low-dose Rituxan may actually be more effective than higher-dose given the way the body’s complement system responds to the drug. The study included six patients with the 17p deletion. Patients were given either 20mg/m2 or 60mg/m2 of Rituxan three times a week for four weeks (the usual dose is 375mg/m2, so this is really low dose.) The results flew in the face of conventional wisdom, which is that Rituxan doesn’t work in 17p cases: “The two patients with the highest cell surface CD20 expression achieved CR (complete response),” the authors wrote, “despite the presence of the del 17p in both cases.”

Let me repeat that: Low-dose Rituxan has been shown to have significant activity in 17p-deleted patients with good CD 20 expression. (Of course, this needs to be studied and verified in larger groups of these patients, but this pilot study has to be welcome news to those in Bucket C-minus.)

So, assuming this good news is correct, and considering that 17p is known to quickly turn aggressive, is there an opportunity cost for such patients in not using low-dose Rituxan early on in their disease?

I cannot solve all these maddening dilemmas, just point them out. A wise person once said that the key in life is not to know all the answers, but rather to ask the right questions. For us patients, just knowing what to ask, and what considerations to balance, is trouble enough in itself. Failing to get some kind of handle on this carries its own opportunity cost: being unable to map out a workable long-term strategy, and being unprepared for the unexpected.

“Opportunity cost” is a concept from economics. Wikipedia describes it as follows: “Opportunity cost is a term used to mean the cost of something in terms of an opportunity forgone (and the benefits that could be received from that opportunity).” So, for example, if a city builds a hospital on vacant land that it owns, the opportunity cost is some other thing that might have been done with the land instead.

How does this apply to chronic lymphocytic leukemia? Have I finally gone off the deep end and decided to talk about building hospitals in my lymph nodes?

Not quite. Let’s take a look at one of our favorite CLL phrases: “watch and wait.” Wikipedia describes this under the medical term “watchful waiting”: “Watchful waiting, also referred to as observation, is an approach to a medical problem in which time is allowed to pass before further testing or therapy is pursued. Often watchful waiting is recommended in situations with a high likelihood of self-resolution or situations where the risks of a therapy potentially outweigh its benefits.”

Well, in CLL, we know that self-resolution is not the usual outcome. We get the short end of the watchful waiting stick: the risks of therapy potentially outweigh its benefits.

The trick is, when do you stop watchful waiting and start treating?

In some patients, this is an easy call -- the hemoglobin and platelets are cras hing, there is fatigue that noticeably impacts quality of life, night sweats resemble the Great Flood, lymph nodes are popping up like well-fed prairie dogs, and so on.

hing, there is fatigue that noticeably impacts quality of life, night sweats resemble the Great Flood, lymph nodes are popping up like well-fed prairie dogs, and so on.

In other patients, the call is a bit more difficult -- perhaps the hemoglobin and platelets are fine, but the lymphocyte doubling time is less than six months, or perhaps the lymphocyte count is normal but nodes are growing into little tennis balls. Looking at prognostic factors such as IgVH mutational status and FISH deletions may provide a little clarity, but sometimes not much.

The NCI Working Group guidelines were written in 1996 to help doctors know which red flags to watch for. But there is no rote approach to starting treatment, and often no general consensus on wh en, exactly, to do it. Doctors have their individual opinions, and medicine is still an art. As we all know, artists range from the paint-by-numbers type to Rembrandt. Many of us have met the former type of hem/onc, and some of us have met the latter. Indeed, I could go on here, comparing some hem/oncs to impressionists like Monet, some to modernists like Picasso, some to surrealists like Dali, and some to elephants at the zoo painting with brushes in their trunks.

en, exactly, to do it. Doctors have their individual opinions, and medicine is still an art. As we all know, artists range from the paint-by-numbers type to Rembrandt. Many of us have met the former type of hem/onc, and some of us have met the latter. Indeed, I could go on here, comparing some hem/oncs to impressionists like Monet, some to modernists like Picasso, some to surrealists like Dali, and some to elephants at the zoo painting with brushes in their trunks.

“Opportunity cost” in CLL

But let’s get back to “opportunity cost.” I will define it in CLL terms: Opportunity cost is what happens when you watch and wait too long. It’s what happens when symptoms get so far out of control that they are either 1) not successfully controllable, or 2) controllable only by extreme measures that, had the disease been treated earlier, would not have to have been taken. By extension, then, opportunity cost in CLL can be the opportunity foregone to treat with less toxic agents.

Patient advocates and some doctors have written about the dangers of premature treatment, which is indeed a problem in the CLL world, especially among hem/oncs for whom CLL is an afterthought or a dim memory in a textbook.

But the problem can, I believe, run in an opposite direction, and the opportunity cost can be an opportunity lost.

An extreme example, just for illustration, would be someone who uses EGCG, to no great avail, but who continues to do so right into marrow failure. Earlier treatment with something -- even Rituxan, or maybe low-dose chlorambucil combined with Rituxan and a low-dose steroid such as dexamethasone -- might have forestalled that day.

Say you’re a patient who would like to stick to the one soft-glove option we currently have readily available, at least in the USA: the monoclonal antibody Rituxan, perhaps  with boosters such as GM-CSF. The problem you have is that even Rituxanites -- or would that be rituximabbers? -- such as myself freely admit that it isn’t all that effective in CLL as a single agent, and doctors heartily echo that sentiment. To the extent that it is effective, it appears to be more so at earlier stages and in patients with less disease burden. So, if you want to use Rituxan, which works best on smaller lymph nodes, is there an opportunity cost to waiting until one’s lymph nodes grow to 8 cm or 10 cm?

with boosters such as GM-CSF. The problem you have is that even Rituxanites -- or would that be rituximabbers? -- such as myself freely admit that it isn’t all that effective in CLL as a single agent, and doctors heartily echo that sentiment. To the extent that it is effective, it appears to be more so at earlier stages and in patients with less disease burden. So, if you want to use Rituxan, which works best on smaller lymph nodes, is there an opportunity cost to waiting until one’s lymph nodes grow to 8 cm or 10 cm?

Rituxan might shrink a spleen that is 6 inches below the costal margin, but will it work on a spleen that reaches halfway to China?

Most responsible physician artists, trained in the days when there was no soft-glove option available, tend to want to watch and wait until the horse is out of the barn, out of town, and in the next county. If the only available choice is hard chemo -- “where the risks of a therapy potentially outweigh its benefits” -- this makes sense.

But today we have the softer-glove array, however limited and imperfect (with the promise of possibly better agents, such as HuMax-CD20, on the way.) So, is there an opportunity cost to letting things go, to following the conservative approach that is the traditional way of watchful waiting?

If you want to play for time by using Rituxan, there may be. Now, some of these doctors might argue that some of us patients can make the mistake of using Rituxan too soon. Nobody said this was easy to finesse. And there is a paradox here: Patients seeking a conservative approach to treatment may treat sooner with Rituxan -- because of the way the drug works -- than traditional treatment conservatives would treat. We may find ourselves at odds with good doctors whose sentiments we appreciate.

One thing that CLL clears the head about is animal testing. When it comes to finding a cure or control for something that might kill you, touchy-feely considerations go out the window. It is entirely selfish, as well as specie-centric, to put mice through the tortures of laboratories for the benefit of man. It is also an effective way of testing new drugs, figuring out new targets for therapy, and of finding a quicker path to controlling or curing this damned disease. I com e from the background of the guilt-ridden meat eater, the wannabe vegetarian who thinks barbequed pork ribs are extraordinarily tasty and who must stare his own hypocrisy in the face every time he sees his reflection in the glass of the butcher's case. I am, like Homer Simpson, a prisoner of bacon. I am also convinced that animals have emotions. I have shared my life with cats and have seen it personally. I have no doubt that the same is true of dogs. There is a marvelous book called When Elephants Weep: The Emotional Lives of Animals by Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson. Masson provides compelling evidence that animals do have feelings, "higher" animals at least. (This includes -- shudder -- pigs.) How high are mice on the chain? Not so high that research on mice bothers me sufficiently to oppose it. If it is a matter of them or me, then until the mice rise up and destroy us, I believe using them in cancer research is necessary.So it is with satisfaction that I read the news that Amy Johnson and the research team at Ohio State University have developed mice with, essentially, CLL. A report in the August 15, 2006 Blood online provides a tantalizing abstract as well as a comment by the renowned CLL expert Dr. John Gribben. It is worth noting the abstract here, in full, emphasis mine:"Drug development in human chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) has been limited by lack of a suitable animal model to adequately assess pharmacologic properties relevant to clinical application. A recently described TCL-1 transgenic mouse develops a chronic B-cell CD5+ leukemia that might be useful for such studies. Following confirmation of the natural history of this leukemia in the transgenic mice, we demonstrated that t

e from the background of the guilt-ridden meat eater, the wannabe vegetarian who thinks barbequed pork ribs are extraordinarily tasty and who must stare his own hypocrisy in the face every time he sees his reflection in the glass of the butcher's case. I am, like Homer Simpson, a prisoner of bacon. I am also convinced that animals have emotions. I have shared my life with cats and have seen it personally. I have no doubt that the same is true of dogs. There is a marvelous book called When Elephants Weep: The Emotional Lives of Animals by Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson. Masson provides compelling evidence that animals do have feelings, "higher" animals at least. (This includes -- shudder -- pigs.) How high are mice on the chain? Not so high that research on mice bothers me sufficiently to oppose it. If it is a matter of them or me, then until the mice rise up and destroy us, I believe using them in cancer research is necessary.So it is with satisfaction that I read the news that Amy Johnson and the research team at Ohio State University have developed mice with, essentially, CLL. A report in the August 15, 2006 Blood online provides a tantalizing abstract as well as a comment by the renowned CLL expert Dr. John Gribben. It is worth noting the abstract here, in full, emphasis mine:"Drug development in human chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) has been limited by lack of a suitable animal model to adequately assess pharmacologic properties relevant to clinical application. A recently described TCL-1 transgenic mouse develops a chronic B-cell CD5+ leukemia that might be useful for such studies. Following confirmation of the natural history of this leukemia in the transgenic mice, we demonstrated that t he transformed murine lymphocytes express both relevant therapeutic targets (Bcl-2, Mcl-1, AKT, PDK1, and DNMT1), wild type p53 mutational status, and in vitro sensitivity to therapeutic agents relevant to the treatment of human CLL. We then demonstrated the in vivo clinical activity of low dose fludarabine in transgenic TCL-1 mice with active leukemia. These studies demonstrated both early reduction in blood lymphocyte count and spleen size and prolongation of survival (p=0.046) as compared to control mice. Similar to human CLL, an emergence of resistance was noted with fludarabine treatment in vivo. Overall, these studies suggest that the TCL-1 transgenic leukemia mouse model has similar clinical and therapeutic response properties to human CLL and may therefore serve as a useful in vivo tool to screen new drugs for subsequent development in CLL."If words aren't enough, the graphics accompanying Gribben's comment include a telling chart showing how the mice developed drug resistance to fludarabine. Fludarabine has gone from the wonder drug to a necessary evil in CLL therapy as doctors have, over time, discovered its negative as well as positive effects. A mouse model such as this may be able to predict drug resistance in a matter of weeks or months -- sparing us human lab rats from having to discover it the hard way over a period of years. In his comment, Gribben writes: "While there is naturally great excitement in exploiting strains of mice with leukemia to test therapy, these models will also be invaluable to understand mechanisms of responsiveness and resista

he transformed murine lymphocytes express both relevant therapeutic targets (Bcl-2, Mcl-1, AKT, PDK1, and DNMT1), wild type p53 mutational status, and in vitro sensitivity to therapeutic agents relevant to the treatment of human CLL. We then demonstrated the in vivo clinical activity of low dose fludarabine in transgenic TCL-1 mice with active leukemia. These studies demonstrated both early reduction in blood lymphocyte count and spleen size and prolongation of survival (p=0.046) as compared to control mice. Similar to human CLL, an emergence of resistance was noted with fludarabine treatment in vivo. Overall, these studies suggest that the TCL-1 transgenic leukemia mouse model has similar clinical and therapeutic response properties to human CLL and may therefore serve as a useful in vivo tool to screen new drugs for subsequent development in CLL."If words aren't enough, the graphics accompanying Gribben's comment include a telling chart showing how the mice developed drug resistance to fludarabine. Fludarabine has gone from the wonder drug to a necessary evil in CLL therapy as doctors have, over time, discovered its negative as well as positive effects. A mouse model such as this may be able to predict drug resistance in a matter of weeks or months -- sparing us human lab rats from having to discover it the hard way over a period of years. In his comment, Gribben writes: "While there is naturally great excitement in exploiting strains of mice with leukemia to test therapy, these models will also be invaluable to understand mechanisms of responsiveness and resista nce to chemotherapy. Although the initial response rate to fludarabine of patients with CLL is high, eventually patients develop relapse with resistant disease. Here again, Johnson and colleagues have demonstrated the utility of this murine model since these mice demonstrate initial responsiveness to fludarabine in vivo, with resulting modest improvement in survival, but rapidly develop resistant disease. Much work still has to be performed to examine the mechanisms whereby such drug resistance occurs, and in particular whether there is eventual loss of function of p53 as occurs frequently with end-stage CLL. However, this model has sufficient clinical and therapeutic similarities to human CLL to believe that this will open up exciting new opportunities to screen new drugs and novel combinations in vivo and speed therapeutic development in this still incurable disease."When I saw Dr. John Byrd at Ohio State in June, we discussed fludarabine and disease resistance. While it has been theorized that fludarabine may select for the p53 deletion, killing off all the other CLL clones and allowing the worst one to survive, Byrd emphasized that it has not been proven. Byrd told me that a nine-month study is underway comparing CLL mice receiving fludarabine with CLL mice receiving no treatment. Will the study show a greater incidence of p53 deletions in the fludarabine-treated mice? Stay tuned. And say a little prayer of thanks for our furry friends with the enlarged spleens and extra-thick necks.

nce to chemotherapy. Although the initial response rate to fludarabine of patients with CLL is high, eventually patients develop relapse with resistant disease. Here again, Johnson and colleagues have demonstrated the utility of this murine model since these mice demonstrate initial responsiveness to fludarabine in vivo, with resulting modest improvement in survival, but rapidly develop resistant disease. Much work still has to be performed to examine the mechanisms whereby such drug resistance occurs, and in particular whether there is eventual loss of function of p53 as occurs frequently with end-stage CLL. However, this model has sufficient clinical and therapeutic similarities to human CLL to believe that this will open up exciting new opportunities to screen new drugs and novel combinations in vivo and speed therapeutic development in this still incurable disease."When I saw Dr. John Byrd at Ohio State in June, we discussed fludarabine and disease resistance. While it has been theorized that fludarabine may select for the p53 deletion, killing off all the other CLL clones and allowing the worst one to survive, Byrd emphasized that it has not been proven. Byrd told me that a nine-month study is underway comparing CLL mice receiving fludarabine with CLL mice receiving no treatment. Will the study show a greater incidence of p53 deletions in the fludarabine-treated mice? Stay tuned. And say a little prayer of thanks for our furry friends with the enlarged spleens and extra-thick necks.

are, of course, researchers hither and yon working on some interesting concepts such as HSP-90 inhibitors and treatments to attack the ZAP-70 protein. All of these targeted therapies -- some of which won’t pan out, and some of which will -- promise much lower toxicity than traditional chemo.)

are, of course, researchers hither and yon working on some interesting concepts such as HSP-90 inhibitors and treatments to attack the ZAP-70 protein. All of these targeted therapies -- some of which won’t pan out, and some of which will -- promise much lower toxicity than traditional chemo.) scrape by with Rituxan until HuMax arrives, then scrape by with that until the B-1 bomber takes the field, or until a monoclonal targeting something else becomes available, or until a breakthrough in vaccine or molecular or biologic therapy happens, one has made a wise use of these opportunities.

scrape by with Rituxan until HuMax arrives, then scrape by with that until the B-1 bomber takes the field, or until a monoclonal targeting something else becomes available, or until a breakthrough in vaccine or molecular or biologic therapy happens, one has made a wise use of these opportunities. isease with it now -- perhaps putting off that Alphabet Soup Chemo forever if I build my bridges right -- yet knowing that my chances of a MRD-negative remission may be somewhat reduced if I ever need one? (And, let’s add these delightful monkey wrenches: Do I assume that science will/will not come up with additional drugs that might render these costs moot in X number of years? Is a MRD-negative remission all it’s cracked up to be?)

isease with it now -- perhaps putting off that Alphabet Soup Chemo forever if I build my bridges right -- yet knowing that my chances of a MRD-negative remission may be somewhat reduced if I ever need one? (And, let’s add these delightful monkey wrenches: Do I assume that science will/will not come up with additional drugs that might render these costs moot in X number of years? Is a MRD-negative remission all it’s cracked up to be?) of Virginia. Taylor is a leading proponent of the concept of CD20 “shaving,” and suggests that low-dose Rituxan may actually be more effective than higher-dose given the way the body’s complement system responds to the drug. The study included six patients with the 17p deletion. Patients were given either 20mg/m2 or 60mg/m2 of Rituxan three times a week for four weeks (the usual dose is 375mg/m2, so this is really low dose.) The results flew in the face of conventional wisdom, which is that Rituxan doesn’t work in 17p cases: “The two patients with the highest cell surface CD20 expression achieved CR (complete response),” the authors wrote, “despite the presence of the del 17p in both cases.”

of Virginia. Taylor is a leading proponent of the concept of CD20 “shaving,” and suggests that low-dose Rituxan may actually be more effective than higher-dose given the way the body’s complement system responds to the drug. The study included six patients with the 17p deletion. Patients were given either 20mg/m2 or 60mg/m2 of Rituxan three times a week for four weeks (the usual dose is 375mg/m2, so this is really low dose.) The results flew in the face of conventional wisdom, which is that Rituxan doesn’t work in 17p cases: “The two patients with the highest cell surface CD20 expression achieved CR (complete response),” the authors wrote, “despite the presence of the del 17p in both cases.”