I recently saw the movie Rashomon again. In it, a crime is described by four different participants, each of whom sees it quite differently. The Akira Kurosawa film is considered a masterpiece, in part for what it says about the human experience: We can all see the same thing, yet we can produce substantially different but equally plausible accounts of it.

This is certainly true of doctors and chronic lymphocytic leukemia. My CLL is cause for treatment with  Rituxan and fludarabine, according to one doctor. It is cause for Rituxan plus cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone, according to another. Another expert weighs in with Rituxan plus chlorambucil. Three doctors say it is cause for nothing more than watch and wait, though two of them differ on how to proceed when treatment time comes. If I were to see more doctors, I would probably end up with a laundry list of treatments and no general consensus on whether to treat at all. As in Rashomon, my CLL is experienced differently by everyone who examines it.

Rituxan and fludarabine, according to one doctor. It is cause for Rituxan plus cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone, according to another. Another expert weighs in with Rituxan plus chlorambucil. Three doctors say it is cause for nothing more than watch and wait, though two of them differ on how to proceed when treatment time comes. If I were to see more doctors, I would probably end up with a laundry list of treatments and no general consensus on whether to treat at all. As in Rashomon, my CLL is experienced differently by everyone who examines it.

But the subjective truth that ultimately matters here is mine. I have come to know my disease better since diagnosis, as I explained in the second part of this series on the “new normal.” And I have gotten to know it even better this year. Part of my “doctor quest” has been to learn more about it, to see it through the eyes of people who are experienced at looking at it, so that I can see it better myself.

What I have learned is that I have what is called “high risk” CLL. The year 2006 brought with it news of clonal evolution, from a “normal” FISH result to deletion 11q. In an IgVH unmutated patient, which I am, this is not good news. Conflicting ZAP-70 tests performed by Quest Diagnostics have been resolved by the lab at UC San Diego, which is considered probably the most reliable place to get your ZAP-70 done: I am ZAP-70 positive.

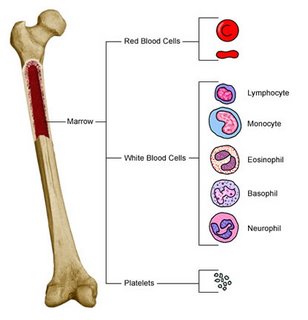

Beyond that, I have clinical signs of progression: a slowly expanding spleen, slowly expanding lymph nodes, and a booming lymphocyte count. I may feel fine now, my hemoglobin and platelets may be in the normal range, and I may not have any “B” symptoms. But this won’t last. How long it won’t last is a matter of conjecture.

As I explained in the The “new normal,” Part 2, I once thought, with some justification, that my disease might be, if not indolent, at least fairly cooperative. After all, I had likely had it for a decade and was still feeling good, even at Stage 2. Yet, I have now learned that the problems I am having -- acquisition of the 11q, disease progression -- are indeed consistent with having had CLL for a decade, especially in an unmutated patient. In fact, it is a wonder things didn’t get worse sooner. If the statistics are to be believed, and if I were a cat, I would have used up four or five of my nine lives already.

But, as Mark Twain quotes Benjamin Disraeli as saying, "There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics." I am not giving up. I am looking to refashion my hope in response to this newest “new normal,” to find a realistic path to a better future. If the climb is at a steeper angle, and my heart beats a little faster, then it will only make me stronger.

Afternoon at The James

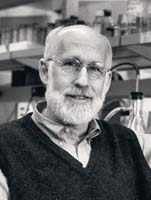

The last doctor I visited was John Byrd at the James Cancer Center at Ohio State University in Columbus. I have followed Dr. Byrd’s research, and he would be on anyone’s list of the top CLL doctors in the country. More importantly, if doctors were choosing which doctors they respect the most, I believe he would be very high on that list, too. Byrd, a self-described conservative when it comes to treatment, has a reputation for adhering to rigorous scientific and ethical standards in his clinical trials. I could have gone elsewhere, and had I gone a little to the south and west of Ohio, I might even have found an expert who would have promised to “cure” me through chemoimmunotherapy. (And no, I’m not talking about a fly-by-night clinic in Mexico.) But my CLL is hard enough to see -- think Rashomon again -- without adding rose-colored glasses to the equation.

And so, Marilyn and I drove 1806 miles from our house to OSU; the last f ew hundred yards were the hardest, since we had to find our way from the parking garage to the James, which sits at one side, slightly hidden, of a huge medical complex. It would have helped had they placed bits of cheese in various locations so we could have known if we were heading down the right corridor at any given time. But we did find it, and with half an hour to spare before my appointment was to begin.

ew hundred yards were the hardest, since we had to find our way from the parking garage to the James, which sits at one side, slightly hidden, of a huge medical complex. It would have helped had they placed bits of cheese in various locations so we could have known if we were heading down the right corridor at any given time. But we did find it, and with half an hour to spare before my appointment was to begin.

It turns out that Dr. Byrd's floor was in mid-renovation, to the point that slips of paper with handwritten numbers tacked to the doors served to identify which exam room was which. The place was phenomenally busy and we were seen phenomenally late. I expected this, of course, and was reminded of the advice offered by a good restaurant I once visited: We take the time to prepare each meal properly, so please be patient.

Eventually my vital signs were taken, and I found that even in the halls of an enormous cancer center, the new normal has its comic moments. We have all heard of a “spit take,” in which a comedian takes a drink of water and, upon hearing something surprising, spits it out. This almost happened to me when I got my temperature taken. After the thermometer was stuck in my snout, I noticed that the nurse’s ID badge was emblazoned with the name “IP Freely.” It took everything I had not to send the thermometer flying across the room.

After a lengthy interview with Dr. Byrd’s nurse practitioner, Mollie, who knows more about CLL than most doctors I have encountered, we were ushered into an examination room to meet Dr. Byrd himself. The doctor looks a little older in person than he does in photographs, and was dressed in a striped oxford shirt, khakis, and tasseled loafers. Missing were the white coat and that usual doctor neckwear -- a stethoscope thrown jauntily about the shoulders. The one piece of medical equipment that Byrd keeps on his person is a cloth tape measure -- "hardware store issue," he says -- for measuring lymph nodes.

Dr. Byrd was personable and did his best to answer all my questions and address all my concerns. It helped that I came with an open mind for an honest opinion and that I was not shopping for news I wanted to hear. Doctors, even the experts, respond to perceived patient expectations. The more open you are, and the more relaxed -- yeah, I know, that part is not always easy -- the more you will usually get out of a visit. We got a lot accomplished during our hour, and by the time I left, I had several points to ponder:

- Unmutated 11q CLL in a person my age (49) will likely mean a stem cell transplant down the road, in my case from an unrelated donor. It’s a risky therapy, but there is a 50% chance of a cure, or something close to it; a 20% chance of outright failure; and a 30% chance of complications that will eventually lead to, as the doctor put it, “badness.” (For more on transplants, check this article at CLL Topics.) That said, the 11q is not reason in and of itself to jump into transplant mode right now.

- It is indeed better, as I have been surmising, to save heavy-duty chemotherapy for a pre-transplant remission and not to burn that bridge now, which would leave me with less chance of effective CLL cell reduction prior to transplant. Such “cytoreduction” is a key element in transplant success.

- In the short term, there is no reason not to continue to watch and wait. My nodes, for example, aren’t nearly as big as I thought they were. The NCI Working Group guidelines for node treatment are 10 cm and most of mine are less than half that. I still feel fine, without “B” symptoms, and my platelets and hemoglobin are normal. At the point at which I start feeling fatigue, satiety (fullness) from an enlarged spleen pressing on the stomach, discomfort from nodes, night sweats, low platelets -- the usual CLL stuff -- treatment will be in the offing.

- I might be able to wait six to nine months -- or even a year or more, if the disease plateaus -- before that happens. When it does, there is no reason not to pursue a biologic approach to therapy ("immunotherapy"), either via a clinical trial or through single-agent Rituxan again. Dr. Byrd has done a dosing study of Rituxan, and thinks infusions three times a week for four weeks may be more effective than the once-a-week-for-eight-weeks that I have had. There is no guarantee that this will work, but I have responded pretty well to Rituxan in the past and it may be worth a try. (I have since been reading some Rituxan dosing studies and will post to the blog about them.)

- Dr. Byrd is not a fan of R+HDMP and he has given me pause in that department. I believe the word he used was “vehemently,” as in “vehemently opposed” to my using it. Suffice it to say that a trial at OSU as part of the CLL Research Consortium led to serious problems in five of nine patients and had to be stopped early. Dr. Byrd knows that off-study R+HDMP is popular among patients, but says they are operating with very little data. In my case, were I to pick up a fungal infection from this immunosuppressive regimen, it could rule out a transplant. HDMP is, Byrd wrote in a report to my local oncologist, “associated with significant infectious risks as well as other end-organ toxicities.”

- In general, Dr. Byrd is excited about some of the trials going on at OSU, including flavopiridol and Chiron-12.12, a CD 40 antibody. He does think things are progressing nicely in CLL research. “There are a lot of things happening,” he said, “so I think the longer you hold out, the better you are.”

Still, I get the sense from any number of experts that progress is incremental. And, alas, many clinical trials of promising agents are designed for the fludarabine-refractory. There are no silver bullets on the horizon just yet, and my disease is progressing faster than science.

It also remains a difficult case, in which I may have no choice but to take some big risks someday. My predisposition to squamous cell skin cancers makes therapy with fludarabine or Campath -- as well as a transplant -- into higher-risk propositions. (It does little good for the CLL to be knocked back if I develop systemic metastatic squamous cancers in its place.) New information about the Epstein-Barr virus and patients with a past history of full-blown infectious mononucleosis -- that's me -- makes me doubly wary of risking T-cell suppressive therapy. (Richter's Transformation doesn't sound like fun.) Dr. Byrd pointed out that CLL is a journey, and there are no doubt some challenging bridges to cross in mine.

Conclusions

Based on what I have learned from Dr. Byrd and from elsewhere in my travels, I now have some sort of plan, albeit one with some still-open questions:

First, I am going to have my HLA typing done and my local oncologist will do a preliminary search of the National Bone Marrow Donor Program database. (I’ll write more to the blog about this experien ce, too.) The search results will let me know how many, if any, good matches pop up, and will give me some idea of what to expect in the future: a fairly easy time of finding a donor, or a difficult one. If it were to appear, for example, that finding a well-matched donor is likely to be impossible, I might consider a different approach to disease control.

ce, too.) The search results will let me know how many, if any, good matches pop up, and will give me some idea of what to expect in the future: a fairly easy time of finding a donor, or a difficult one. If it were to appear, for example, that finding a well-matched donor is likely to be impossible, I might consider a different approach to disease control.

Not all the doctors I have spoken to are fans of transplants, by the way. One commented frankly that, “in order to get the graft-versus-leukemia effect you have to put up with graft-versus-host disease, and in my experience that can be so bad that you are alive wishing you were dead.”

Point taken. But in a world of hard choices, I think it is probably better to risk being alive wishing you weren’t than the other way around. Not all transplant experiences are bad ones, though they have their share of unbearable moments, and it is worth the gamble to me if I have no other option.

There is, of course, another big "if" for me: My insurance company specifically excludes stem cell transplants from coverage. There are plusses to being self-employed, but finding adequate insurance coverage is not one of them. I will have to cross this bridge somehow, if and when I come to it.

Second, the longer I wait for a transplant, if my disease will allow it, the better. The procedure will only improve with time, as will, presumably, its effectiveness. So a 50% chance of success today may be a 60% chance a few years from now. I am young as these things go, and have a 10-year window before I get to the age where transplants are considered too risky to perform. In the meantime, I need to get in the best shape of my life and avoid comorbidity factors such as diabetes and heart disease that would reduce my chances of transplant success. And in keeping the transplant at bay, I need to be creative, as do my doctors, about treatment. It needs to be strong enough to keep me going, not so strong that it burns bridges I need to save. Finessing this will be tricky, and will be a challenge during the next few years. (So when is that Humax stuff going to get on the market, anyway?)

Third, I will watch and wait for awhile longer. I am unused to this -- letting the disease go further than it has gone before -- but I suppose this is part of my newest “new normal.” And the shark I thought I had jumped -- single-agent Rituxan -- has now re-entered the picture. If the statistics on the more intensive Rituxan dosing schedule hold true, there is a 40% or so chance that I can get a partial remission that might last for 10 months. Hardly sterling, but it’s not like there are many softball choices out there. (I will, of course, keep my eyes pealed for clinical trials of interesting alternatives.)

Beyond Rituxan, there are precious few tools readily available in the low-tox toolbox. There are lower-dose steroids, there’s chlorambucil, and perhaps cyclophosphamide. (As you can see, I am grading on a curve here when I say “low tox.”) If I use some of these now but save fludarabine and Campath for pre-transplant use, will that be enough to get the thorough disease clearance I will need?

Fourth, if the last couple of years have taught me anything, they have taught me this: I need to be ready, at the drop of a hat -- or the fax of a test report -- to adapt to any new “new normal” that may come up. As Roseanne Rosannadanna said, “It’s always something.” For example, while I am grateful to learn that having the 11q deletion does not predispose me to picking up the dreaded 17p, new information indicates that a third of unmutated patients will pick up the 17p on their own, even without treatment.

Finally, I have come to the point where I can own my CLL, all several hundred billion mutant Bucket C lymphocytes of it. There is a tendency, when one feels fine, to ignore bad news, bad test results, unimpressive response to treatment. It is only human to want to believe the best about one’s situation. Coming to grips with my ever-changing new normal has been harder, in many ways, than the mechanics of learning about the disease and consulting with doctors. But being honest with myself and seeing it for what it is as best I can -- Rashomon-like -- is essential to taking the right steps to control and perhaps even conquer it.