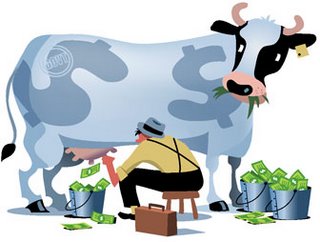

And so it occurred to me that as a patient with a chronic disease who needs treatment regularly and who has a fairly long life expectancy, I am a cash cow in the cancer business. Most other patients at this office either beat their cancer, or don’t, and their files probably cover fewer treatments over a shorter period of time. Having chronic lymphocytic leukemia makes me a frequent flyer, so to speak, a prize customer.

So where are my rewards? I mean, airlines have private lounges for their best customers. Even Camping World has something called the President’s Club. Why not a President’s Club for CLL patients?

For example, I migh

t enjoy a private infusion room -- nay, suite -- with a genuine leather recliner, none of that vinyl stuff. And why can’t my IV pole be at least gold-plated? Where, oh where, is my plasma TV? My private nurse? The dessert tray, fer chrissakes?

t enjoy a private infusion room -- nay, suite -- with a genuine leather recliner, none of that vinyl stuff. And why can’t my IV pole be at least gold-plated? Where, oh where, is my plasma TV? My private nurse? The dessert tray, fer chrissakes?“Champagne with your Rituxan, sir?”

“Don’t mind if I do.”

Clink!

But no, I’m stuck in there with the hoi polloi, some of them using cheap, off-patent drugs. I am a Rituxan user. My insurance pays $5,000 a pop for this stuff; in the last three years I have brought this office around $150,000 in gross income. Yet the management is forcing me to root, raccoon-like, for bags of peanuts from an oversized communal snack basket. What is this, the Motel 6 of oncology?

In all seriousness, or at least partial seriousness, there are times when having CLL can be used to one’s advantage. After one recent Rituxan treatment, Marilyn and I went to our favorite hotel in Phoenix. I plopped my bandaged hand on the counter and announced to the twenty-something clerk that I had been doing chemotherapy and that I needed a quiet room in which to rest. This led to a free upgrade.

When Marilyn and I flew to Florida recently during the height of the gels-on-planes scare, we were able to bring a bottle of Purell hand sanitizer on board with us. This required showing the TSA guards a report stating I have CLL and am immune-compromised, which was backed up by me pointing to my neck and saying, “It looks puffy because I have swollen lymph nodes from my leukemia.”

Indeed, at the Miami airport one of the Northwest Airlines clerks fell all over himself being helpful and gladly agreed to give our bags priority handling even though we weren’t flying first class.

The best story I’ve heard came from a fellow patient in the infusion room, not a CLLer, who lost her hair to chemotherapy. While speeding down the freeway, she was pulled over by a cop.

“Officer,” she said, whipping off her baseball cap to reveal her bald head, “I am late for my chemotherapy.”

It worked, of course. No ticket.

Let that be an inspiration to you the next time Cytoxan does nasty things to your hair follicles.

And while I still wish I could get a complimentary foot massage while being hand-fed Godiva chocolates, I'll take what I can get.