“Dr. Hamblin disagrees with you. He has written in January 2006 (search his blog) that the patient should have his spleen removed, have transfusions, just about be on his deathbed before starting treatment. Read his blog entry if you don't believe it.”

I follow Dr. Terry Hamblin’s blog, and I have read the entry in question, as well has his other entries on the subject, and I generally agree with his approach to treatment. In fact, one of the most important things he has done through his blog and his participation in the ACOR list has been to raise patient awareness about the limits of treatment, and to argue effectively that it should usually be the last resort, not the first.

Anonymous is assuming incorrectly that the purpose of my last post was to promote early treatment; it was merely to show that there can be opportunity costs associated with treatment decisions, including ones in which we avoid treatment at all costs (pun intended).

If we didn't have any soft-glove treatments for chronic lymphocytic leukemia -- which was the case until a few years ago -- I would probably agree with what Anonymous said Dr. Hamblin said. I would have to be at least half dead, preferably three-quarters, before starting treatment.

Of course, it is easy to say something like that, and another thing to do it. Take a splenectomy, for example. Removing a huge spleen involves major surgery, and doing it in a patient whose marrow has crashed to the point of needing transfusions makes it a much more dangerous operation than it would be in an earlier-stage patient. Is there not an opportunity cost if this hypothetical patient succumbs to operation complications or a hospital-related infection by having waited too long to deal with the spleen?

These irksome opportunity costs are lurking everywhere we CLLers turn, and they are to be ignored at our own peril. Explaining this concept was the purpose of my last post, and elaborating on it is the purpose of this one.

Float like a butterfly

Back to the point about soft-glove treatments. In 2006, we do have one -- the CD20 monoclonal antibody Rituxan (rituximab), which is likely to be followed soon by HuMax-CD20 (ofatumumab), which is now accruing patients for Phase III trials and has been accorded fast-track status by the FDA.

(Chaya Venkat of CLL Topics has written a few tantalizing lines about an even more powerful monoclonal coming down the pike, nicknamed the “B1 bomber.” And there

are, of course, researchers hither and yon working on some interesting concepts such as HSP-90 inhibitors and treatments to attack the ZAP-70 protein. All of these targeted therapies -- some of which won’t pan out, and some of which will -- promise much lower toxicity than traditional chemo.)

are, of course, researchers hither and yon working on some interesting concepts such as HSP-90 inhibitors and treatments to attack the ZAP-70 protein. All of these targeted therapies -- some of which won’t pan out, and some of which will -- promise much lower toxicity than traditional chemo.)In some patients and under some circumstances, these low-tox therapies can change the game. I view these drugs as tools -- methods, essentially, of extending watch and wait. (Or, put another way, methods of disease control, however imperfect.) While they don't come with no cost, the risk-reward scale tends to put them into a different category from traditional treatment.

To quote Dr. Hamblin, from his blog entry referenced above:

“If treatment is inevitable, my choice would be the treatment that is least harmful. At the moment this is rituximab. It only works in about half the patients, and it does lower the levels of normal B cells, but this is transient and they quickly return. Rituximab plus a growth factor like G-CSF or GM-CSF may well be more effective. So if it works for you and gives you a year off treatment then go for it, and don’t be afraid to repeat it. True rituximab resistance is very rare. In some patients increasing the dose will turn a non-responder into a responder.”

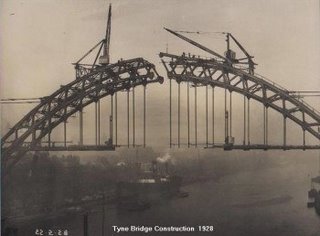

Building bridges and blowing them up

Rituxan and the coming next generation of monoclonals mean that patients may be able to build bridges into the future while still preserving hard-chemo options should they become necessary. If one can

scrape by with Rituxan until HuMax arrives, then scrape by with that until the B-1 bomber takes the field, or until a monoclonal targeting something else becomes available, or until a breakthrough in vaccine or molecular or biologic therapy happens, one has made a wise use of these opportunities.

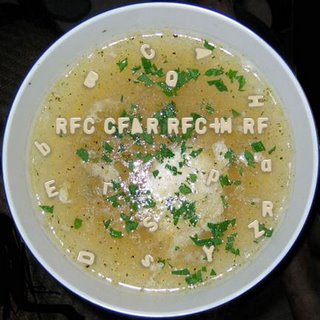

scrape by with Rituxan until HuMax arrives, then scrape by with that until the B-1 bomber takes the field, or until a monoclonal targeting something else becomes available, or until a breakthrough in vaccine or molecular or biologic therapy happens, one has made a wise use of these opportunities.Conversely, if one hits the CLL hard at the start with what I like to call Alphabet Soup Chemo -- RF, RFC, CFAR, RFC+M, R-CHOP and the like -- one has paid a big price in terms of opportunity cost: The soft-glove drugs work best in people whose immune systems are relatively intact, and Alphabet Soup Chemo can lead to all sorts of immune problems, including neutropenia, T cell depletion, and such nasties as myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS). While CFAR is blasting away at your CLL, it is also burning your soft-glove bridges.

That said, drug response in CLL -- depth of remission, tolerance and side effects, development of disease resistance -- can be idiosyncratic and unpredictable. Rituxan is no panacea, and for some it is pretty much a wasted effort.

For others, it is a lifeline, allowing them to maintain a good quality of life for a long time. I am a Bucket C case, and my disease has progressed a bit despite my three courses of Rituxan. But I believe that Rituxan has slowed that progress. (In the irony department, is “progress” really the right concept here?) I am IgVH unmutated, now with the 11q deletion, and I have been at Stage 2 since my diagnosis three years ago. Would I have progressed by now to a later stage without the Rituxan? There is no way to know for sure, but I decided long ago that the opportunity cost of doing nothing was too great to risk finding out.

Single-agent Rituxan is not, of course, an acceptable approach to some doctors. (Among these, it seems, are a few like Lt. Col. Bill Kilgore of Apocalypse Now, who love the smell of napalm in the morning.) They would argue that there is an opportunity cost to using soft-glove treatments prematurely, that this use may render them less effective in combination therapy when and if the time comes that a patient needs a stellar, MRD-negative remission.

From what I gather, though, patients using Rituxan as a single agent do not close the door on this; the synergy between Rituxan and chemo agents seems to boost the effectiveness of both, though there may indeed be some diminution. The patient is left looking at opportunity costs and wondering: Do I let the disease go until I might need Alphabet Soup Chemo, reserving my Rituxan for the best possible remission then? Or do I try to control the d

isease with it now -- perhaps putting off that Alphabet Soup Chemo forever if I build my bridges right -- yet knowing that my chances of a MRD-negative remission may be somewhat reduced if I ever need one? (And, let’s add these delightful monkey wrenches: Do I assume that science will/will not come up with additional drugs that might render these costs moot in X number of years? Is a MRD-negative remission all it’s cracked up to be?)

isease with it now -- perhaps putting off that Alphabet Soup Chemo forever if I build my bridges right -- yet knowing that my chances of a MRD-negative remission may be somewhat reduced if I ever need one? (And, let’s add these delightful monkey wrenches: Do I assume that science will/will not come up with additional drugs that might render these costs moot in X number of years? Is a MRD-negative remission all it’s cracked up to be?)So far -- and again, this is my personal view -- I can only see three cases where enduring the toxicities and potentially deadly complications of Alphabet Soup Chemo is worth it:

One is in a pre-transplant situation, where extreme cytoreduction is a key to success.

The second is in cases where a person’s disease is past the point of being controlled by soft-glove treatments, or by palliative means such as transfusions, and in which the benefits of Alphabet Soup Chemo decisively outweigh the risks.

The 17p dilemma (and a bit of good news)

The third, perhaps -- and this is a big “perhaps” -- is in the case of early-stage, high-risk patients. In fact, there is some debate among experts about whether early intervention may be warranted in patients with the worst cytogenetics, such as unmutated, 17p-deleted cases. In a newly-diagnosed, asymptomatic, Stage 0 patient with unmutated 17p (or even 11q) CLL, is there an opportunity cost to doing nothing? After all, the disease always progresses, fewer drugs work on 17p, and both 17p and 11q patients tend to get shorter-duration remissions. Is it better for the patient to pull out the alphabet soup and blast the disease early, go for something of a cure?

Of course, this being CLL, there is always another way of looking at things.

Here’s an interesting tidbit from a pilot study of 12 patients by Ron Taylor and company at the University

of Virginia. Taylor is a leading proponent of the concept of CD20 “shaving,” and suggests that low-dose Rituxan may actually be more effective than higher-dose given the way the body’s complement system responds to the drug. The study included six patients with the 17p deletion. Patients were given either 20mg/m2 or 60mg/m2 of Rituxan three times a week for four weeks (the usual dose is 375mg/m2, so this is really low dose.) The results flew in the face of conventional wisdom, which is that Rituxan doesn’t work in 17p cases: “The two patients with the highest cell surface CD20 expression achieved CR (complete response),” the authors wrote, “despite the presence of the del 17p in both cases.”

of Virginia. Taylor is a leading proponent of the concept of CD20 “shaving,” and suggests that low-dose Rituxan may actually be more effective than higher-dose given the way the body’s complement system responds to the drug. The study included six patients with the 17p deletion. Patients were given either 20mg/m2 or 60mg/m2 of Rituxan three times a week for four weeks (the usual dose is 375mg/m2, so this is really low dose.) The results flew in the face of conventional wisdom, which is that Rituxan doesn’t work in 17p cases: “The two patients with the highest cell surface CD20 expression achieved CR (complete response),” the authors wrote, “despite the presence of the del 17p in both cases.”Let me repeat that: Low-dose Rituxan has been shown to have significant activity in 17p-deleted patients with good CD 20 expression. (Of course, this needs to be studied and verified in larger groups of these patients, but this pilot study has to be welcome news to those in Bucket C-minus.)

So, assuming this good news is correct, and considering that 17p is known to quickly turn aggressive, is there an opportunity cost for such patients in not using low-dose Rituxan early on in their disease?

I cannot solve all these maddening dilemmas, just point them out. A wise person once said that the key in life is not to know all the answers, but rather to ask the right questions. For us patients, just knowing what to ask, and what considerations to balance, is trouble enough in itself. Failing to get some kind of handle on this carries its own opportunity cost: being unable to map out a workable long-term strategy, and being unprepared for the unexpected.

9 comments:

Oh my goodness! What a long post!

You are an optimistic sort, aren't you? You are banking on treatments that don't even exist!

One day, there will be more mild treatments that actually work, unlike rituxan.

I'm not sure were Dr. Hamblin gets his information (and I know for a fact he has been wrong on several occasions). Resistance to rituxan is certainly possible. I know a fellow CLLer who was on rituxan maintenance, and now is on Campath because the rituxan stopped working. Read the acor.org archives. Everyone on rituxan maintenance eventually requires the drug more and more often, until it doesn't work at all. There are no cures with rituxan. At least some patients end up with a CLL clone that doesn't express CD20. So is that resistance or not? I say it is.

In fact, isn't that exactly the place you find yourself in, right now?

We are in the terrible place where there are hints of a light at the end of the tunnel. But we are far enough away to be unable to distingush that light from that of the on-coming train.

My belief is that once you start treatment, you are fixed in the present. All glimmers of hope are now out of reach. What you have as options are what is standard and available to everyone, unless you risk your neck on a clinical trial and multiple CT scans.

The bottom line is that once you start treatment, you are essentially in the end game. It's sad and unfortunate, but that's the way it is.

I've never seen a survival chart with progressing patients charted that isn't frightenly steeply downhill.

Realistically, once you start treatment, get your affairs in order, retire from the job, and take that trip of a lifetime if you are healthy enough.

BTW, not to be picky or anything, but an acronym refers only to shorthad abbreviations which can be pronounced. 'AFLAC' can be pronouced, even by a duck, so it is an acronym. IBM can't be pronounced as a word, so it isn't an acronym; it's just initials.

Another example is 'SCUBA' as in the diving gear. It stands for "self-contained underwater breathing apparatus".

The mistake is almost as annoying as those who don't understand that "it's" is ONLY used as an contraction of "it is". The possessive of "it" is "its".

Don't be me started on "10 items or less", which is obviously "10 itmes or fewer".

Anybody who writes a lot gets used to being quoted out of context, and of course, what is true one month may not be true the next. But David's approach is one that I largely go along with.

I get my information from a careful study of the published work and by keeping my ear to the ground at meetings, committees and even the ACOR lists.

Resistance to Rituximab (in the sense that cells fail to express CD20) is very rare. There is a well known paper from Ron Levy's group that reports this happening in follicular lymphoma, but apart from the antigen shaving described in Ron Taylor's studies (see above) this is not a problem in CLL.

We don't know for certain how rituximab kills CLL cells, and it may be different in the blood and in the tissues, but some patients' cells develop defects that prevent all apoptosis that relies on the mitochondrial pathway. This mechanism of resistance not only prevents rituximab killing, it also stops killing by chlorambucil, fludarabine and anthracyclines. In these circumstances we have to rely on other pathways. ageents that use these other pathways are high dose steroids, Campath, flavoperidol and X-irradiation.

AS far as splenectomy is concerned, it provides a means of removing a large bulk of disease without damaging normal bone marrow, and also makes available a lot of platelets that are pooled in a big spleen, and removes a killing field for red cells. I don't advocate it for everybody, but in certain people it is a good idea that is often neglected.

Some people decide that the right choice for them is alphabet soup. I respect their decision. There are advantages and disadvantages to this approach, it is certainly not a no-brainer.

This is to the first post at the top. Could you go somewhere else and post your hopeless and tactless thoughts. For some people there are more than one trip of a lifetime,some people love their job and some keep their

affairs in order and are not sick.

David has on his blog beginning with" I am not a doctor and I do not play one on the internet." If you are so smart

make your own blog.Just a thought, you could name it

Start Treatment and Die. The blog for the Hopeless that Want to Bring People Down to Their Hopeless Level.

I adore David's and Dr. Hamblin's posts and am grateful they take the time to share whatever info they have, even if it changes.Cll changes and so do treatments. Do me a favor and crawl back under your rock,don't mess up our good thing.

Most Sincerely,

Carlin C.

First, Anonymous #2 – who sounds a lot like Anonymous #1 -- is right about acronyms, and I stand corrected. So much so that I am changing “Acronym Chemo” to “Alpahebet Soup Chemo.”

Second, as to some of the points Anonymous #1 made:

I am making educated guesses about the treatment landscape in the near future. HuMax is coming. Chiron-12.12 is in trials. Fenretinide and AT-101 are in trials. Flavopiridol is in trials. Etc. Etc. Some other things are more theoretical than fact as of right now. But one thing is certain: the longer one waits, the more new drugs come online. Ten years ago, we didn’t have Rituxan or Campath for CLL. Ten years from now, we are likely to have some new things we don’t have today. How a patient can get from here to there is the question. Is there an element of chance to it all? Yes. Is it an impossible dream, so to speak? Not by any means.

Rituxan does, in fact, work – work being defined as the palliation of symptoms. That’s all that any chemotherapy has been demonstrated to do. In some people, Rituxan works better than others. As to the situation I find myself in, Dr. John Byrd has suggested higher-dose Rituxan as my next treatment. To boost my response, and if I wish to dip my toes in the shallow end of the chemo waters, I can add low-dose chlorambucil (my idea, not his). Or steroids in high or low doses, or GM-CSF, or beta-glucan. These are all potential Rituxan boosters.

Dr. Hamblin has addressed the question of disease resistance and Rituxan. I would add this: My understanding is that all CLL clones express some CD20, even if it is a very low amount. HuMax-CD20 has been shown to be effective on those with low CD20 expression. HuMax is coming.

You wrote: “My belief is that once you start treatment, you are fixed in the present.”

If time stopped, you would be. But at my house, the little hand and the big hand of the clock keep going in circles. If a treatment buys you a remission period of X amount of time, then drug A or B may become available during that time. The game can change under your feet. I know some patient histories, too, people who have had the disease long enough to take advantage of successively better treatments.

You wrote: “All glimmers of hope are now out of reach. . . . The bottom line is that once you start treatment, you are essentially in the end game. It's sad and unfortunate, but that's the way it is.”

You really must read Dr. Jerome Groopman’s “Anatomy of Hope,” or at least my review of it.

Dr. Byrd also told me that CLL is “a journey.” For some it is longer than for others. With the advent of soft-glove therapies, we may be able to change those survival charts in which you place so much faith.

And maybe we won’t. But where do we end up if we don’t try?

(P.S. Carlin, thank you for your comments, also – I got quite a laugh out of your prospective blog titles.)

I realize I'm a little late to the party here, but to get my 2 cents in, I never hold much credence in what people, who are afraid to post their identities, have to say.

Seriously, I'm talking about people who are in the midst of treatment, and the unlikelihood of a significant improvement in treatment in a few years.

Is it impossible? No.

I just am personally realistic. I would like a miracle cure, but I realize that that may not be possible.

It takes time for new drugs to come to the marketplace; even Rituxan and Campath took years to routinely be used to treat CLL. And the drugs are still being fine-tuned.

Take what I said in a negative light if you wish. I am a realist, and don't believe there will be a cure for CLL in my lifetime.

The way to experience the latest in treatment is through a clinical trial.

Wow, this is hot stuff! I'm late with my comments, as I've been away enjoying a weekend at Cape Cod. Gee, I've had many helpings of the alphabet soup plus a transplant ... hmmm, why am I feeling so great and enjoying stuff like Cape Cod, etc??? I must have forgotten to retire and pack it in 13 years ago when I started down that soup line. Sorry Anonymous, I just couldn't help myself. I take no offense at your slant on things. It actually enriches the landscape of discussion as evidenced by David's and Dr. Hamblin's further feedback. In spite of my long CLL history (dx 1989), I've been a dummy, until discovering the likes of Dr. Hamblin, David A. and Chaya. What they each bring to our table is priceless. I thank my lucky stars every day for how much they do for me.

Cape Cod sounds nice. I'm out of town also and just toured the Salvador Dali Museum. It's almost as surreal as CLL.

Seriously, though . . . there is a place for comments, like those of Anonymous 1, that stray from the norm, so to speak. Anything that helps us broaden our thinking, and that includes challenging our assumptions or perceptions, has a valuable place. This is a learning experience, whether we end up agreeing on all points or not.

Thanks, all, for reading and participating.

Post a Comment