skip to main |

skip to sidebar

In a few days it will be my fiftieth birthday. This being CLL, I will spend it in Phoenix with my hematologist/oncologist. And Marilyn, of course. We will be discussing treatment, and then two of us will be having dinner somewhere.

Fifty is a landmark, probably moreso than forty, when life is supposed to begin. Fifty is a half-centur y, as solid and respectable as one of those old gray office buildings that make up the skyline of any Eastern city. It has an established, enduring quality. I feel as if I should go buy some stock, or take up golf.

y, as solid and respectable as one of those old gray office buildings that make up the skyline of any Eastern city. It has an established, enduring quality. I feel as if I should go buy some stock, or take up golf.

In reality I will probably continue on my road to eccentricity. Oh, how many cats I could adopt if there were just a slight dimunition in my judgment. I will talk to myself while walking around the house trying to remember what it was I was looking for -- and I will enjoy the conversation. I will take less and less moderate positions on the great issues of the day. I will become twice the hippie I might have been in my youth and will trip without the LSD.

Having chronic lymphocytic leukemia changes fifty. What might have been a midlife crisis point has become rather welcome, a milepost of survival. I made it another year, and into another decade, and so there is reason to celebrate.

The gifts will be simple: My beloved Marilyn, and good friends, and family. My older half-brother (along with his kind and personable wife) has reappeared in my life. I did not spend a lot of time with Rick as a kid -- he is 11 years my senior -- and we have had only sporadic contact as adults. He has had an interesting life, taking some wild and woolly paths rather different from my own. Meeting as we are again in our older age, I find we have a great deal in common. Our outlooks toward the state of civilization and the meaning of things are similar in many ways. He’s smart, and he has a big heart and a good sense of humor, and he wants to do what he can to help me fight this CLL.

Our mother died, suddenly, at the age of 57, when I was in college. When I look into his face I can see her eyes. I remember when she died, thinking 57 was so young. I never guessed that I might acquire a disease that would, statistically, make my own survival to that age a question mark.

I know some wonderful people with CLL who say they are dying bit by bit, losing the war of attrition. They hold out little hope of a cure, and they live with some debilitating aspects of the disease, notably fatigue. They see it as their inevitable end.

I do not see it as mine. Call me eccentric, but the one thing that is incurable about me is my optimism. Defying the conventional thinking is something that appeals to me more and more as I get older and older. Fifty may not make me a gray monolith; it may free me to float away from established paradigms.

One of my earliest memories is being in a hospital, in a crib, and being determined to get out. I climbed up the back of the crib, grabbed onto a lamp attached to the wall above it, and then made my way to the window sill above that. A nurse passed by the open door to my room, and I will never forget the look of horror on her face as she saw me leaning against the window several feet above my bed.

Rick said that when I was a toddler I was a little Houdini, always getting out of cribs, and out of my room, much to the annoyance and amazement of my parents. I had a facility for escape.

Hear that, CLL?

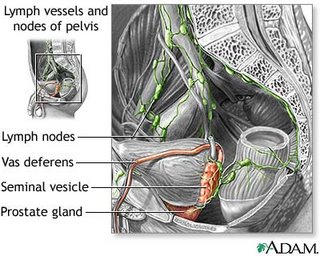

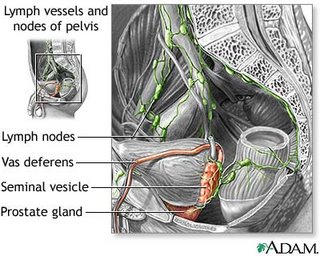

Well, actually, that should be abdominal lymph node. Or perhaps deep pelvic lymph node from hell. Wherever it is, it is starting to really annoy me.

I first noticed the Abominable Lymph Node (ALN) in February 2005. I was laying on the sofa reading a nonfiction book, 50 Acres and a Poodle, about a woman who says goodbye to city life and moves to a Green Acres-type place. Her boyfriend develops a strange pain in his abdomen, which turns out to be a tumor on the intestine.

The ALN was then only noticeable when I lay flat on my back; there was just a slight sensation of pressure near my left hip, nothing painful. If I lay on my side, or stood up, or sat in  a chair, I did not notice it. Still, it was a new sensation, not unlike the new sensation the boyfriend in the book had begun to notice. And it definitely wasn’t normal.

a chair, I did not notice it. Still, it was a new sensation, not unlike the new sensation the boyfriend in the book had begun to notice. And it definitely wasn’t normal.

“Oh, it’s probably just a lymph node,” I told myself as I read each page with increasing interest, my growing paranoia kept barely in check.

I convinced myself to get a CT scan just in case I was being blindsided by another health misfortune. After all, chronic lymphocytic leukemia had come as a complete surprise and I had no way of knowing if Pandora’s Box was still open, letting all sorts of nasty things out.

It turns out there was a happy ending to the book. The boyfriend’s tumor was benign. And there was a reasonably happy ending for me, too: it was just a node. I was about to start my second course of Rituxan therapy and I expected it to take care of the problem.

But four rounds of Rituxan later, the ALN was still there, though it had hardly earned its name at that point. As time went on I got used to it. The pressure increased almost imperceptibly. When I started eight rounds of Rituxan in October 2005, I hoped that might take care of it. No such luck.

During the early part of this year, the ALN grew from a minor sensation to a slight bother. I would notice it when sleeping on my right side, and when sitting. When Marilyn and I drove to Columbus, Ohio to see Dr. John Byrd, it was there -- not especially troublesome but present nonetheless. I asked Byrd about it, and he stuck his hand into the flesh next to my left hip and said, matter-of-factly and without any concern, “Yes, you have some deep pelvic lymph nodes.”

I asked Byrd whethe r I needed CT scans to monitor those and other nodes, and he said it wasn’t necessary. If, for example, a node were pressing on a kidney and becoming a problem, it would show up in the creatinine numbers on a chem panel.

r I needed CT scans to monitor those and other nodes, and he said it wasn’t necessary. If, for example, a node were pressing on a kidney and becoming a problem, it would show up in the creatinine numbers on a chem panel.

My chem panels before and since have been marvels of normalcy. Whatever the ALN is pressing on, it apparently isn’t all that important. But it is noticeable, and during the last week or so it has entered the realm of chronic pain. Not horrible nerve-shooting-down-the-leg pain, which I have heard about in CLL. Just pressing and pressing and pressing, noticeable no matter where I sit, stand, or lay. I am not sure what water torture is like, but this could be similar. For the first time this past week I couldn’t sleep because of the pain and had to take an ibuprofen.

Now I realize that in the grand scheme of chronic pain this is nothing. It is not interfering with my life and daily business, just making things more uncomfortable. I rather enjoy ibuprofen and that will work for awhile, I suppose, but it is not a solution. Neither is asking my doctor for percocet or oxycontin. I can enjoy a few hours of spaciness as much as anyone, but it is not a way to live one’s life. I suppose there is acupuncture, or perhaps hypnosis, but these are, again, temporary solutions to a problem that will only get worse.

So the ALN has done what I have been expecting one of these days to happen: it is the symptom that heralds the end of watch and wait. The ALN is the other shoe that finally dropped. Nodes, abominable and otherwi se, appear to be my major symptom. My hemoglobin and platelets are still well within normal with no downward trend, meaning that marrow impaction is not an issue. (In fact, my latest CBC shows platelets going up.) I still have no B symptoms. Just a very thick neck (to match my thick skull) and a rather distended abdomen.

se, appear to be my major symptom. My hemoglobin and platelets are still well within normal with no downward trend, meaning that marrow impaction is not an issue. (In fact, my latest CBC shows platelets going up.) I still have no B symptoms. Just a very thick neck (to match my thick skull) and a rather distended abdomen.

What is the aim of treatment? To reduce the nodes (and tamp the disease back down again). And to do this as part of my near-term treatment strategy. That strategy, simply put, is to use HuMax-CD20 when it arrives on the market, perhaps in 2008. My goal is to get from here to there, and then to use HuMax for as long as I can. Burn no bridges, play for time, the same old song, now with rhyme! I meet with my local hem/onc later this month to formulate a treatment plan. What exactly that is yet, I don’t know. But it will involve Rituxan and very likely something else. The Abominable Lymph Node has got to go.

I don't often post here just to recommend someone else's post, but I am making an exception today. Dr. Terry Hamblin has provided an elegant and simple explanation in his blog of why using fludarabine may not be such a good idea unless you really and truly have your back to the wall.

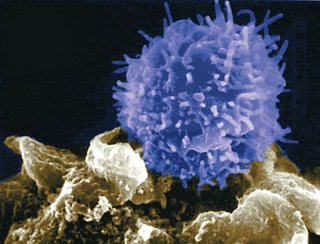

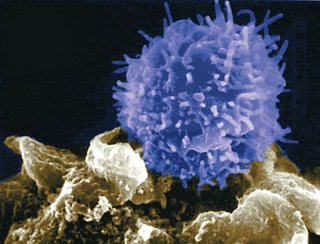

What adds an especially worthwhile dimension to Hamblin's piece is that it puts CLL into context, so to speak. This context -- the "what does this disease really mean?" -- is something we patients are always trying to get a handle on. Hamblin points out that patients don't usually die of extra white cells wandering around, they die of things related to reduced immunity. Immunity is degraded by the disease over time, even before treatment. For example, immunoglobulins (IgG, IgA, IgM) are known to slowly decline as the disease ramps up. Nonetheless, our bodies can learn to accommodate large amounts of CLL, and our immune systems can  still function reasonably well for a long time. For many of us, there is a certain workable stasis. If we choose to nuke the CLL, we also nuke what is left of the immune system. But the bacteria and viruses that were lurking on planet Earth and in our bodies before therapy are still there afterward. This is one constant that does not change. It is a given that immunity is made worse by treatment. CLL patients who have gone through fludarabine regimens often look like AIDS patients when it comes to their T cell count. It does you no good to get a "sterling" remission if you die of an infection some months later. (As an aside, follow-up is not the strong suit in some clinical trials. And "acceptable toxicity" is easy for researchers to say, and quite another thing for you to live with.) CLL Topics has been reporting recently about the dangers that lurk after therapy -- take a look here and here and here. If I were to make a list of the major news stories in CLL during the past year, the growing recognition among experts of problems stemming from T-cell depleting therapy, which also includes Campath, would be at or near the top.

still function reasonably well for a long time. For many of us, there is a certain workable stasis. If we choose to nuke the CLL, we also nuke what is left of the immune system. But the bacteria and viruses that were lurking on planet Earth and in our bodies before therapy are still there afterward. This is one constant that does not change. It is a given that immunity is made worse by treatment. CLL patients who have gone through fludarabine regimens often look like AIDS patients when it comes to their T cell count. It does you no good to get a "sterling" remission if you die of an infection some months later. (As an aside, follow-up is not the strong suit in some clinical trials. And "acceptable toxicity" is easy for researchers to say, and quite another thing for you to live with.) CLL Topics has been reporting recently about the dangers that lurk after therapy -- take a look here and here and here. If I were to make a list of the major news stories in CLL during the past year, the growing recognition among experts of problems stemming from T-cell depleting therapy, which also includes Campath, would be at or near the top.

Death by fludarabine is not merely theoretical. I know of patients, plural, who have used fludarabine and died of the complications, both immediate and long term. I know of others whose lives have been made miserable by the effects of reduced immunity, and elsewhere in his blog Hamblin posits that once fludarabine does its thing, the immune system never recovers to where it was before. Now I also know many people who have used fludarabine, and who have used it in combination with Rituxan and perhaps cyclophosphamide, and these people sailed through therapy. They feel great and have no regrets.

Fludarabine does have a place in CLL therapy and when you have to use it, you are glad it is there. Fludarabine is basically a good thing. What concerns me is the reflexive, even wanton, use of it by people who don't think these things through. The bottom-line question is: What will make you live longer? So often we patients and our well-meaning doctors can see no further than the tips of our noses. It is worth repeating this point ad nauseam: Depth of any given remission does not necessarily mean you will, over the course of your battles with CLL, live longer. Always ask yourself: What is the potential long-term price of your choice? Not just in terms of burned bridges, but in terms of reduced immunity and its complications? Are you jumping out of the frying pan and into the fire? Some of us -- perhaps including me one day -- will have no choice but to make that leap, but why do it before you absolutely have to? Hamblin points out that, as time has gone on, chlorambucil actually might be pr oviding longer overall survival than fludarabine, and he argues that there should be a study of chlorambucil plus Rituxan. Such studying, to the extent that there has been any, has been in individual patients convincing their individual doctors to give it a try. Anecdotally, at least, reports posted in such places as CLL Forum and the ACOR list show it to be an effective enough therapy. Rituxan seems to potentiate everything it comes in contact with. (It would be interesting to see how R+CB stacks up against RF in terms of immune and other complications, as well as depth and length of remission.)

oviding longer overall survival than fludarabine, and he argues that there should be a study of chlorambucil plus Rituxan. Such studying, to the extent that there has been any, has been in individual patients convincing their individual doctors to give it a try. Anecdotally, at least, reports posted in such places as CLL Forum and the ACOR list show it to be an effective enough therapy. Rituxan seems to potentiate everything it comes in contact with. (It would be interesting to see how R+CB stacks up against RF in terms of immune and other complications, as well as depth and length of remission.)

Dr. Hamblin's interest in and support for this combination has given it a push in the patient community. Prior to his arrival on the scene, R+CB was mainly promoted by Kurt Grayson, a patient and friend of mine who years ago had the smarts to ignore the advice of a prominent doctor who told him he'd be dead any day if he didn't do heavy-duty chemo ASAP. Kurt was greeted with derision for his "old fashioned" choice from some fellow patients who figured bigger is better. Now, as the old song goes, everything old is new again. Even today, those of us who choose the more conservative route -- be it Rituxan as a single agent or an "unorthodox" combo like R+CB -- still face an uphill climb when it comes to credibility in the offices of many hem/oncs. But do remember that the road less traveled may get you further, and that the assumptions of today may be turned on their heads tomorrow.

This post isn’t about CLL -- thus the "OT" for "Off Topic" -- but then I am not all about CLL. Sometimes I complain about other things. The ability to kvetch transcends one’s state of health. Indeed, the ability to work up a fair degree of indignity is probably a sign of health. When I used to work at a hotel catering to a crowd of older folk, there were several good candidates for a T-Shirt emblazoned with these words of wisdom: “The more I complain, the longer God lets me live.”

But I am digressing from my digression.

Marilyn and I enjoy the NBC TV show Medium. For those who don’t know, it’s about a psychic, Allison DuBois, who works for the district attorney’s office in Phoen ix, Arizona. Allison, played by Patricia Arquette, is married to Joe Dubois (Jake Weber), and they can never get a decent night’s sleep. This is because Allison is always waking up from strange dreams that may or may not turn out to be premonitions, or postmonitions, or whatever, and which always have some bearing on the plot. The DuBois’ have three young daughters, two of whom also have psychic abilities. The family scenes are well-drawn, showing exactly what life must be like in households were metaphysics coexists with the mundane, where the wife is dreaming about severed heads while the husband wants some nookie.

ix, Arizona. Allison, played by Patricia Arquette, is married to Joe Dubois (Jake Weber), and they can never get a decent night’s sleep. This is because Allison is always waking up from strange dreams that may or may not turn out to be premonitions, or postmonitions, or whatever, and which always have some bearing on the plot. The DuBois’ have three young daughters, two of whom also have psychic abilities. The family scenes are well-drawn, showing exactly what life must be like in households were metaphysics coexists with the mundane, where the wife is dreaming about severed heads while the husband wants some nookie.

What makes it a little more interesting for us is that the show is set in Phoenix, which is the fifth largest city in the United States, and which Marilyn and I know fairly well at this point, since we live two hours north of it and go there frequently. Phoenix is a big, sprawling place. Like much of Arizona, it is surrounded and interspersed with craggy mountains that look blue-gray from a distance. These lend the city its character, such as it is. I will not pretend that Phoenix is a great urban treasure, like Venice or San Francisco, but it is a decent enough place. The climate is hot but not humid, homes are fairly affordable, and the air is clean once in awhile. It has a symphony and an opera and a world-class American Indian museum and one of every major sports franchise, even ice hockey. There are at least 15 Vietnamese restaurants now, which is sort of the scale I go by in grading cross-cultural advancement amon g American burgs. Metropolitan Phoenix is defined as everything within Maricopa County, and includes such cities as Scottsdale, the toniest suburb; Tempe, which is the home of Arizona State University; Mesa, which is bigger than St. Louis but has no there there; and Sun City, the retiree mecca where they roll up the sidewalks at five.

g American burgs. Metropolitan Phoenix is defined as everything within Maricopa County, and includes such cities as Scottsdale, the toniest suburb; Tempe, which is the home of Arizona State University; Mesa, which is bigger than St. Louis but has no there there; and Sun City, the retiree mecca where they roll up the sidewalks at five.

Medium is set in Phoenix because there really is a "research psychic" named Allison DuBois who lives there; and the more Marilyn and I watch the show, the more we realize how careless the writers are about all things Arizona. For those who have never looked at a map, Arizona is adjacent to California, where people in Hollywood produce shows like Medium. It’s not like they’re being asked to describe life on Mars.

By the time I get to Ely

Some of the inaccuracies are understandable enough and simplify things for plot purposes. The name of the county has been changed from Maricopa to Mariposa, presumably for liability reasons. Maricopa County has a county attorney, and in Medium this person is known as the “district attorney.” In the show, the mayor of Phoenix and the deputy mayors of Phoenix are always breathing down DA Devalos’ neck. In reality, Phoenix is just one of the cities served by the county attorney, and the mayor of Phoenix has no authority over that attorney. In fact, nobody knows who the mayor of Phoenix is. (OK, it’s Phil Gordon, but nobody cares.)

Beyond this, the show gets into some things that can only be described as bloopers, small and large. Some are the kind you only notice if you live in the area. In one episode, the University of Arizona is described as being in Phoenix, when it is actually in Tucson, two hours south. Would the writers have placed USC in Fresno? I doubt it. In another episode, one of the DuBois daughters gets an opportunity to speak to the "state Assembly.” California has a state Assembly. Arizona does not. It has a state House and a state Senate, collectively known as the state Legislature. In yet another episode, Phoenix police respond to a call in Scottsdale. Would the writers have had the LAPD show up in Long Beach? Again, probably not.

Medium also makes little effort to show what Phoenix looks and feels like, which is why on Medium it feels like Los Angeles. They do try to get in a lot of shots of palm trees, but there is seldom a blue-gray peak, and hardly ever a Southwestern-style ranch house, and no hint of the vast sky and its play of light at sunset. The Medium Phoenix is a bit too verdant, the light is a bit too dim, and Allison is always wearing sweaters and jackets, which people do not do all that often in the hottest metropolis outside Mecca. Allison never gets in her car in the summer, touches the shift lever, and screams in pain.

trees, but there is seldom a blue-gray peak, and hardly ever a Southwestern-style ranch house, and no hint of the vast sky and its play of light at sunset. The Medium Phoenix is a bit too verdant, the light is a bit too dim, and Allison is always wearing sweaters and jackets, which people do not do all that often in the hottest metropolis outside Mecca. Allison never gets in her car in the summer, touches the shift lever, and screams in pain.

The worst blooper I have seen (so far) occurs in an episode where a killer is describing the route he took while driving from Phoenix to Los Angeles with a victim. At one point he starts waxing about “wher e the road turns into one lane.” Perhaps in 1906, but not 2006, where something known as Interstate 10 connects the two metropoli. Worse yet, he goes on to use the phrase “by the time we got to Ely, Nevada.” I have included a map here showing the route from Phoenix to LA via Ely, Nevada. Does anybody check facts on the show? Or do they simply not care?

e the road turns into one lane.” Perhaps in 1906, but not 2006, where something known as Interstate 10 connects the two metropoli. Worse yet, he goes on to use the phrase “by the time we got to Ely, Nevada.” I have included a map here showing the route from Phoenix to LA via Ely, Nevada. Does anybody check facts on the show? Or do they simply not care?

The larger relevance of these mistakes is that they call into question just how much Hollywood gets wrong about everything everywhere.

"Facts are stupid things" -- Ronald Reagan

As the brouhaha about the ABC movie The Path to 9/11 shows, accuracy in the portrayal of events is crucial when it comes to the writing of history. (Rewriting history is easy, but it is an affront to those who died in the making of it.) Accuracy is certainly more important in a project that purports to tell what really happened in the run-up to a major terrorist attack than in a TV show about a psychic. But I wonder if all this isn't symptomatic of an underlying disease in which our society has become too careless with the facts. I used to be a newspaper reporter and editor, and I was trained with the idea that you did not just accept someone’s word about something, you double-checked the “facts” that were presented to you before running with the story. This was a sacred tenet of the work. If one didn't always do it well, one always made the effort.

If I had stayed in journalism, I would have slit my wrists by now. The most recent example of a media that didn’t do its job is the case of John Mark Karr, the pathetic loser who claimed he killed JonBenet Ramsey. A little healthy skepticism, and some digging, might have nipped this in the bud a little sooner, or at least presented some balance to the piece. Yes, there were a few doubters, notably Dan Abrams on MSNBC. But for the most part we were treated to a spectacle in which inane details, like how many times Karr got up from his seat on the plane to LA to use the bathroom, became the news of import. Infotainment is replacing hard news, and in the span of a generation we have gone from Walter Cronkite to Katie Couric. “Journalist” has come to mean “newsreader.” In such an environment, what really happened on the road to 9/11 can be forgotten if it is inconvenient to the plot -- or point -- that a particular writer or director is trying to make. We live in a state of fiction masquerading as fact. (I have no problem with people taking particular views, but label them as such -- "editorial commentary" or "opinion" -- and if I may quote my favorite jurist, Judy Sheindlin, don't pee on my leg and tell me it's raining.)

The signs are ominous: with so many competing media outlets that need to fill never-ending news (and entertainment) holes that are as big as black holes, we cannot be bothered with accuracy, with fact-checking, with getting something right. (Ironically, the more cable news channels, the less actual news reported.) In a world of spin, truth has become a relative thing.

thing.

This is most tragic in the news division. The television media especially seem to lack the fortitude or even the basic talent to question what they are fed. The result is a regurgitation of spin from one side or the other, thus compounding inaccuracy and confusion. No wonder the American public mistrusts the media almost as much as it does politicians.

Media laxity and herd-think has done our country another great disservice. Without launching too far into another tangent, let me say that the press did not do its job in the run-up to the Iraq War. We are now paying the price for the Fourth Estate’s cowed cheerleading. I am Joe Blow sitting out here in the middle of the desert and I smelled a strategic and political rat from the very beginning. Did anyone of influence in the major media take a detached, critical view of the situation in 2002 and early 2003? Friday afternoon’s news dump was a report by the Senate Intelligence Committee that showed there was no connection between Saddam Hussein and Al-Qaeda -- in fact, Saddam distrusted Al-Qaeda -- and that the Bush Administration had been told this by intelligence services before it went to war. Surely some enterprising reporters could have gotten somewhere near the bottom of this a little bit closer to the event. And now we learn this how many lives later?

But back to Medium. It’s a good show. It’s entertaining. It’s not accurate about the place in which it is set, but it would seem we Americans no longer prize accuracy above expediency. In TV-land, this is merely annoying. In the real world, the consequences can be damning.

Today is the third anniversary of my diagnosis with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. It feels like any other day, which is only appropriate considering that CLL has become part of my daily routine. There were times, in the beginning, when I feared I wouldn’t live another three months. And there were times when, after visiting uninformed doctors, I felt confident that I would live another thirty years.

I am not sure how it will all pan out, but I am pleased with the three-year increment. It is a bite-sized stretch of time, long enough to feel like a long time, short enough to plan for. I have lived three years with CLL. I have every expectation of living another three. I can see myself getting from here to there. Flying anvils may yet do me in, but when it comes to CLL, I am not beaten.

If wondering how I will make it another thirty years can be depressing, knowing I will make it another three is reassuring. And if three years from now I can see a clear route to three more, then mayb e I will make a long journey in small steps. Perhaps I will surprise myself one day at how far I have come in increments of three.

e I will make a long journey in small steps. Perhaps I will surprise myself one day at how far I have come in increments of three.

The next three years will no doubt be different in some ways that I cannot imagine. But I do know that the unending process of figuring out if and when to treat the disease and with what will be part of the picture. I am used to this landscape, less afraid of it than in the past but rather more annoyed at the time and energy it takes to navigate and negotiate. In most cancers you fight, you win or lose, and you're done. CLL is like the movie Groundhog Day, in which the main character relives the same day over and over. You fight, you buy some time, and then you have to do it all over again. In some ways, having CLL is akin to the labors of Sisyphus, the king in Greek mythology who was forced to push a boulder up a hill for eternity.CLL is not complicated, but there is nothing simple about it. It is considered to be a “systemic disease” because the mutant B cells are everywhere, but it is systemic in more ways than one. It is systemic in the time, money, and energy it takes, in the stress and anxiety it causes, in the well-laid plans it disrupts.

Perhaps the next three years will see an evolution in the way Marilyn and I cope with the totality of what it means to have leukemia. Perhaps I need to learn to better compartmentalize CLL’s role in my life, to put it away in the attic more often, to practice the old adage “out of sight, out of mind.” Marilyn and I deserve some time a lone without the elephant in the room. Marilyn especially does, for this is harder on her than it is on me. CLL is something I have made and that I have to live with, and that I have become familiar with. If to me it is an intimate enemy, to her it is an alien who threatens to steal me away. We see it from different vantage points, and whenever we go traveling and get away from it for awhile, we both see that it takes a great deal from us. So in the next three years I hope we can learn to live better with it than we have, by whatever strategies make sense.

lone without the elephant in the room. Marilyn especially does, for this is harder on her than it is on me. CLL is something I have made and that I have to live with, and that I have become familiar with. If to me it is an intimate enemy, to her it is an alien who threatens to steal me away. We see it from different vantage points, and whenever we go traveling and get away from it for awhile, we both see that it takes a great deal from us. So in the next three years I hope we can learn to live better with it than we have, by whatever strategies make sense.

And that is the point: to live well. I do not mean sipping champagne on the Riviera, though that would be nice. I mean living with a good degree of harmony, in comfortable surroundings, doing things that are, on the whole, more life-enhancing than stress-creating. This is all the more a challenge given CLL, but it is not impossible.

Perhaps that is the lesson of the last three years: Nothing is impossible, and that includes the prospect of beating this disease. I will take that thought to heart, three years at a time.

y, as solid and respectable as one of those old gray office buildings that make up the skyline of any Eastern city. It has an established, enduring quality. I feel as if I should go buy some stock, or take up golf.

y, as solid and respectable as one of those old gray office buildings that make up the skyline of any Eastern city. It has an established, enduring quality. I feel as if I should go buy some stock, or take up golf.