The blogosphere, as Forrest Gump might put it, is like a box of chocolates: You never know what you’re going to get.

So imagine my surprise when a hematologist/oncologist, just the sort of animal that we CLL patients depend upon, decided to read my article at CLL Topics called Diagnosing your doctor. Dr. Vance Esler of Amarillo, Texas, was inspired to write a reply in his blog. His first post is called The Empowered Patient. He followed this with Why Your Doctor Doesn’t Want to Talk as Much as You Do.

Since I have a history of diagnosing doctors, and since I think choosing doctors wisely is essential to success in CLL, I was interested in his comments. Basically, Esler says a little knowledge is a dangerous thing but that informed patients are OK so long as they don’t try to practice medicine with his license.

That last point is a valid one, I think; we cannot expect to direct our doctors. We do need their expertise and advice. But we can expect to work with them. This means they should listen to our concerns, and we should listen to theirs.

“I have mixed feeli

ngs about working in the era of the empowered patient,” Esler writes. “It helps when patients are educated enough to make intelligent decisions and to cooperate with the plan. On the other hand, it is tiresome having to negotiate or justify every little thing . . . The information explosion, combined with a desire to treat my patients correctly, forces me to read constantly. It used to offend me and fill me with dread when patients would walk in with reams of stuff they had pulled off the internet. Now I am used to it. 99% of the time I can honestly say, "Yep, I am aware of that." Now I realize that people are just being diligent.”

ngs about working in the era of the empowered patient,” Esler writes. “It helps when patients are educated enough to make intelligent decisions and to cooperate with the plan. On the other hand, it is tiresome having to negotiate or justify every little thing . . . The information explosion, combined with a desire to treat my patients correctly, forces me to read constantly. It used to offend me and fill me with dread when patients would walk in with reams of stuff they had pulled off the internet. Now I am used to it. 99% of the time I can honestly say, "Yep, I am aware of that." Now I realize that people are just being diligent.”From what I’ve heard from my CLL friends, and know from my own experience, not all doctors are diligent readers. We live in a sound-bite world, and too often I get the impression that some doctors are barely able to keep up with the headlines, let alone issues of substance that can be at the heart of life-or-death decisions for patients.

No doubt doctoring is a busy business. When I watch mine at work, as I sit for hours in the infusion chair, she is constantly running around the office and barely has time for a bite or two of lunch. And no doubt there are patients that one dreads to see coming. Anyone who works with the public is familiar with this feeling. I used to help run a hotel, and when certain people got within 15 feet of the front desk, I would look for any excuse to step away for a minute. There was one old lady who was such a pain that I wanted to buy her a T-shirt that read: “The more I complain, the longer God lets me live.”

But neither time constraints -- a topic to which Esler devotes a great deal of time -- nor the pain-in-the-ass factor are enough to justify an argument that patients, like good children of yore, should be seen and not heard. There is simply too much at stake for the patient.

Esler has some nice things to say about me and my blog, including that I have “a remarkable grasp (of CLL) for a lay person.” What he may not realize is that I am one of many “empowered patients” with this sort of knowledge, and that there are any number of CLL patients who know as much or more than I do. I just tend to write about it.

There are some compelling reasons why CLL patients, in particular, have felt it necessary to become informed, or empowered, or whatever you want to call it.

The first reason is the quirkiness of the disease itself. In most cancers there may be a very limited set of choices when it comes to formulating what Esler calls “the plan.” It’s almost hard to imagine after a few years in the trenches with CLL, but there may even be some “no brainers” out there: This is what you have, this is what you do, end of story.

In CLL, wise patients have no choice but to think for themselves. In a cancer where even the experts disagree -- think of Dr. Terry Hamblin and Dr. Michael Keating debating the value of heavy-duty chemoimmunotherapy, which they have in fact done in person (click link at very bottom right) -- our very survival can depend upon our ability to question our doctors’ assumptions. This most definitely includes those doctors on the local level who may not be up on the latest, and whose thoughts about treatment may be somewhat outdated. Countless patients have learned the hard way that it pays to be diligent.

[NOTE: If you use the preceding link to CLL Global and read Dr. Keating's version of his debate with Dr. Hamblin, please also see Dr. Hamblin's comment under the "Comments" link at the bottom of this post.]

The search for objectivity

Esler writes: “There is a major caveat to the proactive patient approach: patients who direct their own care lack objectivity. It is said that a physician who cares for himself has a fool for a doctor. Patients who insist too much on directing their care may become just as guilty of that.”

In a narrow sense, I understand what he is saying. Doctors are trained to look at symptoms, blood test results, and the like, and to see a complete picture. Some pati ents may be fixated upon a particular symptom, may not understand where a particular test result fits in the order of importance, may let emotional issues cloud their judgment, and so on.

ents may be fixated upon a particular symptom, may not understand where a particular test result fits in the order of importance, may let emotional issues cloud their judgment, and so on.

But many doctors treating CLL are just as clueless. My own experience with Dr. Lippencot shows what can happen when a doctor mistakenly gets fixated upon a particular symptom. A medical license is no guarantee of expertise. I would venture to say that a majority of CLL patients posting to internet forums have felt compelled to change oncologists at some point. It’s not that these patients want to direct their treatment and are looking for a pushover with a prescription pad. They simply want to find a doctor who they feel is truly competent in CLL, and who is willing to treat them as a partner in the process of formulating “the plan.”

Patients, through their own experiences and from talking with others online, quickly realize that there are any number of subtleties that can be easily missed, or misconstrued, by doctors. Take staging, for example. Dr. Hamblin has quoted Dr. Kanti Rai, the namesake of the Rai staging system, as saying that his entire system would have to be thrown out if one uses CT scans. Doctors using CT scans for CLL are seeing things that Rai, when he developed his system in the 1970s, could not. The result is that patients can be staged “later,” or the disease can be thought to be worse, than it actually is. Hamblin points out that a CT scan will probably show a swollen lymph node in a Stage 0 patient. In another patient it may show a swollen spleen, but if that spleen cannot be palpated, it is inconsequential in the Rai schema. Yet how many Lippencots out there are rushing to treat based upon blobs they see on X rays, failing to put that information into context? Far too many, I’m afraid.

So wise patients -- by necessity -- need to develop some objective sense of the details of their particular case, and where that case fits into the scheme of things. In CLL, only a fool blindly follows a doctor’s orders.

Beyond the technical questions, I think a patient needs to come to grips with his or her condition in order to participate intelligently in the process of treating it. Some -- the ostrich crowd -- don’t want to know, of course. But many patients want a basic understanding, and some want to know everything they can.

Getting some sense of “where I stand” or “the big picture” is, in fact, part of human nature. The world is made up of many kinds of people. Some, who are probably more passive in their non-cancer daily lives, might prefer that a doctor tell them the answer; others, the more strong-willed to begin with, want to know through their own examination of the evidence. They may seek the counsel of a doctor or two, but reserve unto themselves the final determination of “truth.”

So, for any number of reasons, the search for objectivity has become a major task of informed patients. It consumes many an online discussion. Patients are always talking about such things as: Does this symptom mean I need treatment? Which treatment is best given my type of CLL? What are the consequences, down the road, if I use this treatment today?

The CLL Internetwork

This need to figure out what is going on has given rise to a well-developed network of online resources. What I know about CLL is not the product of original research; it is a synthesis of the information available in such places as CLL Topics, the ACOR list, Dr. Hamblin’s blog, the CLL Research list on Yahoo, and perhaps a dozen other places. In these sites I have found links to countless abstracts and articles, and I have also found intelligent discussions of what all these things mean and how they apply to given cases.

I see my little role in this internet enterprise as one in which I help provide some context. I hope to show, in between occasional tangents, how all this information can be prioritized and organized and used in a practical way by patients trying to figure out what to do.

This CLL Internetwork -- I’ll give it a name, and perhaps it is the real Patientzilla -- is used by doctors as well. There are local oncologists who follow CLL Topics, for example. And Topics science writer Chaya Venkat -- a retired research chemist with a doctorate in education -- has developed a good working relationship with some of the top doctors in the field. She can turn to them for information and counsel, and, in turn, she can suggest ideas about clinical trials, prognostic tests, treatment possibilities, and so on. This shows how the internet is a two-way street, giving patients more information but also enabling receptive doctors and researchers to understand what is on the mind of the patient community.

Dr. Hamblin’s presence on ACOR and through his blog also makes an important statement, that here is where his duty is, and here is where the action is. It helps that he is semi-retired and has the time, but i t says a lot that he spends it on the net working with patients. Dr. Hamblin, in case you don’t know, is one of the top CLL experts in the world. And what he says definitely gets back to oncologists in countless localities, expanding their understanding of CLL through the patient as intermediary.

t says a lot that he spends it on the net working with patients. Dr. Hamblin, in case you don’t know, is one of the top CLL experts in the world. And what he says definitely gets back to oncologists in countless localities, expanding their understanding of CLL through the patient as intermediary.

A quick example of the growth of an idea is the concept of Rituxan plus G-CSF as a useful frontline therapy. CLL Topics has been beating the drum about this (with EGCG and fish oil added to the mix, in a protocol nicknamed "RHK") for years. A ripple effect started as patients began to convince their local doctors to give it a try. Now, in an important new blog post, we see that this concept has been endorsed by Dr. Hamblin, who has been able to review the anecdotal evidence regarding its use over the course of time. This, in turn, will probably help the concept ripple even further -- an idea born on a patient site on the internet, and coming to an oncologist near you.

The point of all this is that the CLL Internetwork is here to stay and is symptomatic of something that is spreading like a cancer (forgive the pun) across cyberspace: the free availability of information to patients with all sorts of ailments.

This will only expand as time goes on. The net effect (yes, another pun) is that patients will become smarter consumers of medical services. This may be uncomfortable for some doctors, especially those who would rather not be bothered answering questions or discussing details. They will no doubt stay in business, though, because there is a doctor shortage in many places. And because there will always be those patients who prefer to not know, who just want the doctor to fix them. It never ceases to amaze me, as I sit for my Rituxan infusion in what the nurses call Chemoland, that a lot of my fellow patients don’t even know the names of the drugs being pumped into their veins.

For some doctors, who do not carry the baggage of thinking they have the truth in a medical bag, this new era may prove exhilarating. (Even the skeptical Esler says that it “can be fun” to work with educated patients so long as they are “nice” and “respect the doctor’s time.”) There are doctors who have an open approach, who say that learning from patients is one of the pleasures of their profession. These doctors actually appreciate the abstr acts, articles, treatment protocols and other information patients have brought to the office. Humility is important in any role we play in life, and that goes for both patients and doctors. We all have room to grow in our knowledge of things.

acts, articles, treatment protocols and other information patients have brought to the office. Humility is important in any role we play in life, and that goes for both patients and doctors. We all have room to grow in our knowledge of things.

Patient empowerment is now a fact in the medical landscape. The cat won’t go back in the bag, the horse is wandering well away from the barn, and the whole damned camel is in the tent. And this means that the era of the paternalistic doctor will slowly -- very slowly, perhaps -- come to an end.

I get the sense from Esler’s posts that he is not exactly embracing this change, but rather accepts it as a fact of life that takes some getting used to. He is undoubtedly not alone. But he is living, as the Chinese saying goes, in interesting times. The dissemination of knowledge cannot be stopped, and knowledge is power. If you doubt that statement, think of China again. There is a reason the Communist government in Beijing wants Google to censor its search results for Chinese net surfers.

Where the buck stops

If you think about it, people should be empowered about their health, whether they have cancer or not. We should all have an understanding of the basics of how the body works and how best to maintain it, and we should realize that this maintenance is an active responsibility. There seems to be a disconnect in Western society at times, in which people tend to regard their bodies as they do their cars: something to be used any way they like, which can then be towed into the shop to be fixed. Would that it were so.

If I were to define the term “empowered patient,” I would say it is someone who has researched their medical condition and who expects to be involved in determining how it is to be handled.

But there is more to it than that. The empowered patient is one who understands where the power to make decisions ultimately lies. When it comes to deciding on treatment, let’s remember who is employing whom. Patients must be comfortable with what is being proposed for their bodies. They have every right to expect a reasonable discussion of the options. If you’re suggesting that I use a drug with potentially major, perhaps even fatal, side effects, I have every right to expect a few extra minutes of your time to talk about it.

Esler says doctors are sometimes loathe to spend much extra time on patients, pointing out that doctors are generally paid by the job and not the hour. This situation, he says, is the result of price controls forced on doctors by private insurers and Medicare, and means doctors earn their money on volume of patients seen, not on the time spent with each patient. Esler says this isn’t ideal, but it’s just the way it is.

I think almost every patient eventually realizes that we Americans are not living in an ideal world when it comes to the health care system. Rube Goldberg could not have devised a “better” contraption, but that is a rant for another post. Esler’s comments bring home the fact that, to get the most out of their care, patients should be as prepared and focused as possible during their office visits.

But beyond that, there are times when it is necessary to say “damn the system, full speed ahead.” I see adequate communication between doctor and patient as something essential to getting the job done right. As I learned in the hotel business, there are low-maintenance guests and there are high-maintenance guests, and at the end of the day it all pretty much balances out.

Given the pressures and shortcomings of the health care system, perhaps it is all the more challenging to find a doctor whose dedication to his or her craft sufficiently outweighs his or her concern about the bottom line. There is a big difference between doing a job and being dedicated to a craft, and this difference in attitude can be found among people in any profession. My dentist has a sign in his office, something to the effect that every patient gets the personalized attention they need, so please be patient. He is always running late. Good for him.

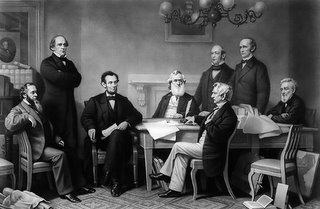

When it comes to the question of power in the doctor-patient relationship, I will close with a story about Abraham Lincoln meeting with his cabinet shortly after he took office. The cabinet considered an issue and voted to proceed in a certain way. Lincol n was alone in disagreeing with them. He pointed out that his views would prevail since, being the president, he was “a majority of one.”

n was alone in disagreeing with them. He pointed out that his views would prevail since, being the president, he was “a majority of one.”

Well, you are the president of your body, serving a lifetime term. You are the one who must make the final call, and you are the only one who has to live with the consequences. Like Lincoln, you can choose to go along with your advisors -- or not.

The balance of power rests with the patient. The doctor proposes, the patient disposes. In the era of the CLL Internetwork, patients can do so with greater wisdom and intelligence. Doctors had better get with the plan.

4 comments:

I have read what Michael Keating said I said in the debate. I don't remember saying any of that. What I did say was that the so called targeted therapy monoclonal antibodies weren't very precise in their targeting. Campath is directed at an antigen called CD52 and like the B52 bomber causes considerable collateral damage. Rituximab is directed against CD20, an antigen that was originally known as B1, and like the B1 bomber with its laser guided bombs is very much more precise, because it inly kills B cells. I then showed a picture of Dresden after World War II fire bombing. Slowly the rebuilt opera House emerged from the ruins thanks to the wonders of PowerPoint. There's the similarity to CLL. No matter how hard you knock it down, it keeps coming back.

I get the sense from Esler’s posts that he is not exactly embracing this change, but rather accepts it as a fact of life that takes some getting used to.

Actually, I'm not against empowered patients at all. You can rest assured I take a hard look at what is being proposed to me or my family. Being a doctor, I am only too aware that there are not-so-good docs out there. I tend to become "empowered" myself when it is my ox that is about to be gored.

My problem is when patients drive but are unqualified. Yes, patients pay the bill (well, really they don't anymore), causing some to think they can call all the shots. But the doctor takes on the liability if anything goes wrong -- which means he has veto power.

The best arrangement, as I think we are all suggesting, is that patients and physicians work together to determine what is best for each individual's interest.

I do take exception to the comment that one who 'blindly' follows the doctor's plan is a 'fool'.

I'm sorry, but you can't prescribe drugs yourself. The doc makes that decision.

And you ain't going to design a treatment plan that involves choosing one drug from column A, and another from column B, etc., unless you are indeed a fool.

Clinical trials have honed treatment plans to at least a best guess, if not a science. Where do you think the FCR and CHOP+R protocols came from? They didn't come from patients (Kurt G. excepted)!

Some patients don't really want to know the details; they are unlike you. Perhaps they are in their late 80s, unschooled in and uninterested in learning about CLL to any appreciable degree.

Are these patients to be dismissed in your mind as 'fools'?

Other patients may trust their doctor to come up with the best plan. After all, that is how it was done 100 years ago.

Perhaps they have made peace with CLL and God, and are ready to take what life gives them.

I suppose to you they are, too, 'fools'.

It's easy for you to cast aspersions on others, isn't it?

Perhaps you should step back and admit that you don't have all of the answers, and that you can't speak with any authority as to how others feel and what comfort zone they are in.

I never said I had all the answers and I freely admit that I don't have the truth in a bag. I just call it as I see it. That's the nature of a blog.

There are many different kinds of patients. Some are more assertive, some are more passive, some are more trusting, some are not.

I have found many, many examples of doctors not knowing what they're doing, be it about CLL or something else. When it comes to life or death decisions, I think it makes sense to question authority, or at least to find out what the consequences are of a particular course of action.

I stand by my statement that in CLL only a fool blindly follows a doctor's orders. Notice I said "blindly." That is the key word here that you seem to have missed. I have seen too many patients who have suffered the consequences of medical mistakes. There's a guy I know of with garden variety CLL who followed his doctor's advice to use Zevalin (radioactive Rituxan). Guess what? It nuked his marrow, he became subject to any and all infections, and eventually died. All within a few years of diagnosis. Had he questioned the doctor's orders, he would be here today.

'Nuff said.

Post a Comment