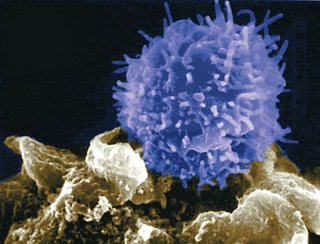

What adds an especially worthwhile dimension to Hamblin's piece is that it puts CLL into context, so to speak. This context -- the "what does this disease really mean?" -- is something we patients are always trying to get a handle on. Hamblin points out that patients don't usually die of extra white cells wandering around, they die of things related to reduced immunity.

Immunity is degraded by the disease over time, even before treatment. For example, immunoglobulins (IgG, IgA, IgM) are known to slowly decline as the disease ramps up. Nonetheless, our bodies can learn to accommodate large amounts of CLL, and our immune systems can

still function reasonably well for a long time. For many of us, there is a certain workable stasis. If we choose to nuke the CLL, we also nuke what is left of the immune system. But the bacteria and viruses that were lurking on planet Earth and in our bodies before therapy are still there afterward. This is one constant that does not change.

still function reasonably well for a long time. For many of us, there is a certain workable stasis. If we choose to nuke the CLL, we also nuke what is left of the immune system. But the bacteria and viruses that were lurking on planet Earth and in our bodies before therapy are still there afterward. This is one constant that does not change. It is a given that immunity is made worse by treatment. CLL patients who have gone through fludarabine regimens often look like AIDS patients when it comes to their T cell count. It does you no good to get a "sterling" remission if you die of an infection some months later. (As an aside, follow-up is not the strong suit in some clinical trials. And "acceptable toxicity" is easy for researchers to say, and quite another thing for you to live with.) CLL Topics has been reporting recently about the dangers that lurk after therapy -- take a look here and here and here. If I were to make a list of the major news stories in CLL during the past year, the growing recognition among experts of problems stemming from T-cell depleting therapy, which also includes Campath, would be at or near the top.

Death by fludarabine is not merely theoretical. I know of patients, plural, who have used fludarabine and died of the complications, both immediate and long term. I know of others whose lives have been made miserable by the effects of reduced immunity, and elsewhere in his blog Hamblin posits that once fludarabine does its thing, the immune system never recovers to where it was before.

Now I also know many people who have used fludarabine, and who have used it in combination with Rituxan and perhaps cyclophosphamide, and these people sailed through therapy. They feel great and have no regrets.

Fludarabine does have a place in CLL therapy and when you have to use it, you are glad it is there. Fludarabine is basically a good thing. What concerns me is the reflexive, even wanton, use of it by people who don't think these things through.

The bottom-line question is: What will make you live longer?

So often we patients and our well-meaning doctors can see no further than the tips of our noses. It is worth repeating this point ad nauseam: Depth of any given remission does not necessarily mean you will, over the course of your battles with CLL, live longer. Always ask yourself: What is the potential long-term price of your choice? Not just in terms of burned bridges, but in terms of reduced immunity and its complications? Are you jumping out of the frying pan and into the fire? Some of us -- perhaps including me one day -- will have no choice but to make that leap, but why do it before you absolutely have to?

Hamblin points out that, as time has gone on, chlorambucil actually might be pr

oviding longer overall survival than fludarabine, and he argues that there should be a study of chlorambucil plus Rituxan. Such studying, to the extent that there has been any, has been in individual patients convincing their individual doctors to give it a try. Anecdotally, at least, reports posted in such places as CLL Forum and the ACOR list show it to be an effective enough therapy. Rituxan seems to potentiate everything it comes in contact with. (It would be interesting to see how R+CB stacks up against RF in terms of immune and other complications, as well as depth and length of remission.)

oviding longer overall survival than fludarabine, and he argues that there should be a study of chlorambucil plus Rituxan. Such studying, to the extent that there has been any, has been in individual patients convincing their individual doctors to give it a try. Anecdotally, at least, reports posted in such places as CLL Forum and the ACOR list show it to be an effective enough therapy. Rituxan seems to potentiate everything it comes in contact with. (It would be interesting to see how R+CB stacks up against RF in terms of immune and other complications, as well as depth and length of remission.)Dr. Hamblin's interest in and support for this combination has given it a push in the patient community. Prior to his arrival on the scene, R+CB was mainly promoted by Kurt Grayson, a patient and friend of mine who years ago had the smarts to ignore the advice of a prominent doctor who told him he'd be dead any day if he didn't do heavy-duty chemo ASAP. Kurt was greeted with derision for his "old fashioned" choice from some fellow patients who figured bigger is better. Now, as the old song goes, everything old is new again.

Even today, those of us who choose the more conservative route -- be it Rituxan as a single agent or an "unorthodox" combo like R+CB -- still face an uphill climb when it comes to credibility in the offices of many hem/oncs. But do remember that the road less traveled may get you further, and that the assumptions of today may be turned on their heads tomorrow.

3 comments:

David,

Well written as usual and Kudos to our friend Kurt for paving the way to less toxic treatments.

Regards,

Deb

David, I just finished reading Dr. Hamblin's article. Very informative especially since I had FCR and never heard any of this before. Love your writing style and the topics are always good. As for that Saturday post with the ugly comments I will say this: I am as conservative as they come, but my comments still stand!

Regards,

Loren

Chlorambucil is an older treatment that has been used for CLL for years. Sometimes both physicians and patients get into a rut thinking "newer is better." But often, the reason some older drugs are still around is that they still work. While many of my colleagues have gravitated to fludarabine and other combinations, I have continued to use chlorambucil with reasonable success. I was like everyone else -- I was intially enthusiastic about fludarabine. But after some reality-check experiences, I have relegated it to the "big gun" category.

Perhaps in disagreement with Dr Byrd, I don't like to wait until the serum creatinine is abnormal before deciding to address pelvic or retroperitoneal lymph nodes. By then, you are already in an urgent situation with compromised renal function. Why let it get to that?

I do not treat lymphadenopathy just because it is there, but if it is large or in a risky position, I will sometimes follow CT scans or ultrasounds to make sure the nodes are not starting to block urine outflow which will eventually cause kidney dysfunction and ultimate failure.

Post a Comment